Photos by Derek Bell

As the soft hum of a needle buzzes with the staccato tempo of thin, short lines permeating his flesh with white and violet, Caleb McMorrow curiously lifts his head from his prostrate position to see The Starry Night come to life on his shin.

Owner of Body Canvas on Broad Street David Nicholson’s hand keenly mimics Van Gogh’s sprawling legacy of cerulean swirls and golden orbs onto the canvas of McMorrow’s skin with undaunted concentration. But come Monday morning, Nicholson’s most recent masterpiece will be smothered underneath McMorrow’s work uniform.

Though ink has long since made its impression throughout centuries upon centuries of human history, work environments that don’t bat an eye at body art are still the exception, rather than the rule. While some locals maintain that society is definitely evolving toward a more accepting position for tatted workers, others say the more conservative ways are going nowhere fast.

In McMorrow’s case, the Rome-Floyd County firefighter sought approval from his superiors before going beneath the needle. “Our rules are, if you have tattoos and you’re already at the fire department, you’re not going to get kicked out but you can’t have anything below your elbows,” he explains. “And they want you to send a picture and get [anything new] approved even if it’s under clothes. My shin and my calf, I had to go get those approved.”

Speaking with the cadence of a skilled multitasker, Nicholson chimes in. “I’ve heard a story, locally, about a woman who was in a car wreck, and when [an emergency responder] came to rescue her from her collapsed car and cut her out, she complained on him because he had visible tattoos on his arms.”

In Nicholson’s line of work, customers relay stories of employers’ distaste toward tattoos, but his clientele tend to dance around borderlines of the office dress code fine print.

“People tend to know up front that it could cause them some issues,” he says. “A lot of times, they just plan around it or they look for jobs that don’t care whether or not they have tattoos… bartenders, hair stylists, they sort of have free reign to decorate themselves any way they want to. I think that’s a good thing; I’d like to see the rest of society be that way.”

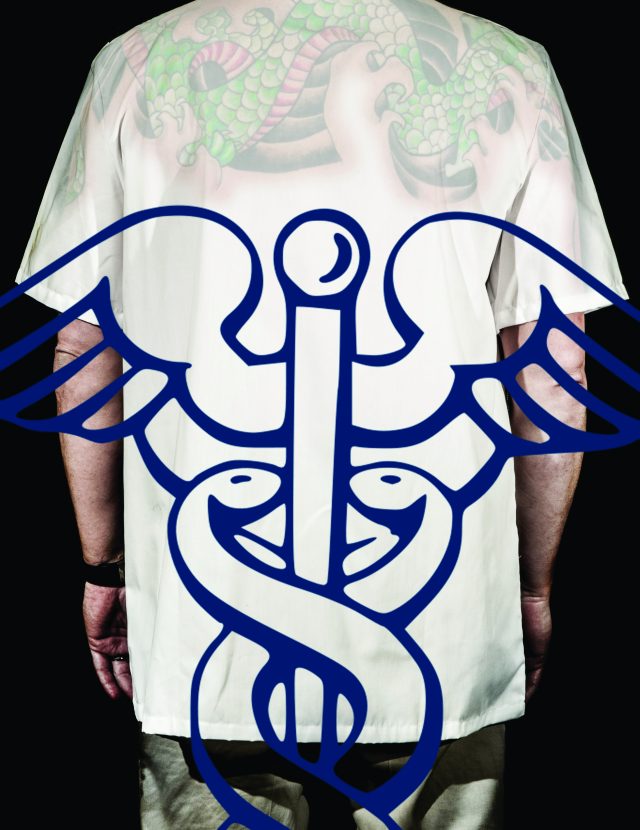

While it’s accepted, almost expected for employees in certain fields to flaunt their ink, other areas, particularly the healthcare industry, leave little room for that sort of creativity.

“I think you’ll always find in the right setting, creativity is always appreciated,” says Beth Bradford, chief human resources officer of Floyd Medical Center. “[In] healthcare, to me it’s all about vulnerability. When you go to the doctor, what you’re doing is putting yourself out there to have a healthcare experience.”

Bradford delineates FMC’s “Manner of Dress” code, where visible tattoos are against the hospital’s policy.

“With regard to tattoos and body art, all visible tattoos and body art must be completely covered during the work period,” she says. “What that would mean for us is if you have a tattoo or design on your face or on the tops of your hands, that’s going to be a problem.”

According to Bradford, FMC does employ some people who have extensive tattoos, but those workers wear long sleeves or cover up in one way or another. She adds that while people from different demographics may have conflicting views on tattoos, the policies of FMC and the healthcare industry by and large lean toward professionalism, and their employees understand and respect that.

A Floyd County pharmacist, who preferred to be quoted anonymously, says though he has 20 years of pharmacy experience, his more than 30 hours of art remain under wraps to maintain that positive image of utmost professionalism.

“For a pharmacist, anywhere you go [for a job], it’s definitely going to be a black mark against you if you’re not able to cover the tattoos with work attire,” he says. “Where I am now, everybody is pretty cool with it, but we don’t have much direct patient contact. I think that’s where the issue lies – in the image that you present to your customers.”

His body art may not be welcomed by the watchful eye of the workplace, but they are accepted as personal stories and aspects of human interest. In fact, he has experienced leniency from his work superiors, whether it be having a conversation about his art or actually having a portion of a shift covered by his district manager to make it to his tattoo appointment. While he contends he would have gotten his tattoos in more visible places if he could have, he outlined the rationalization that tattoos could make some question a business’s professionalism.

“[A] company will shy away from odd styles,” he says, “especially in a pharmacy where someone might interpret it as unprofessional, and whether it is or is not, it tends to be the general public opinion. I think it’ll be a long time before anyone gets away from that.”

On the other side of the gun, sending their art out into the world are tattooists like Nicholson and Wes Lingerfelt of Eternal Expressions. While each tattooist has experienced a recipient on an impromptu whim of embellishment, more often than that, they tattoo individuals who have undergone lots of consideration, personal preparation and financial planning.

Nicholson says the most prominent tend to be religious or family oriented tats. He also alludes to a more psychological reasoning regarding body art. “There are some people who get tattoos because they want to offend people,” he says. “They distance themselves from people who judge on personal appearance; the more tattoos you have the fewer people you have to deal with who are superficial.”

On that same note, Jamie Corrado, a 24-year-old graphic design/digital arts major at Reinhardt University, who describes herself as a shy individual, says she’s found that her tattoos make for convenient ice-breakers.

“Having the tattoos has actually helped me with social skills,” she says. “More people approaching me about [my tattoos] has brought me out of my shell.”

When it comes to the what, where, and possible repercussions of the artwork and placement, the tattooists can only make suggestions about how the ink could affect their customers’ employability.

“Especially young females,” Lingerfelt says, “because young females with visible tattoos can find it extremely difficult to find employment.”

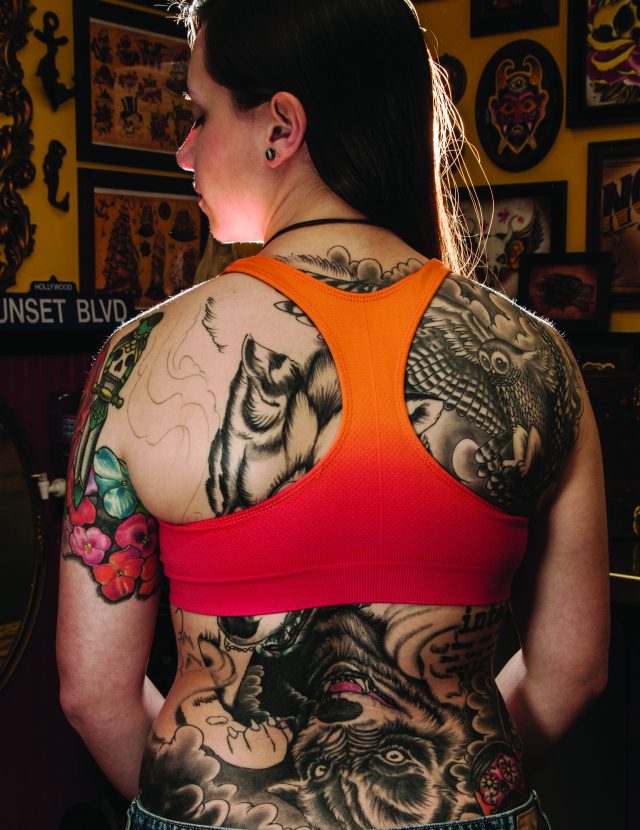

With one year and one semester to go before graduation, Corrado is a heavily tattooed full-time student with two jobs and a career search in her not-so-distant future. Inked with a nautical themed full leg sleeve, a full back piece, a quarter sleeve, and a small tattoo around her wrist, she realizes that her job search may very well land her in long-sleeves and pants – a fate she is prepared for and understands.

Corrado’s love for ink is fueled by her admiration for the artistry, but she respects the need for professionalism and consistency in the workplace and doesn’t use her body art as a way to challenge that. Displaying maturity and accountability, she says, “If you’re choosing to consent to getting tattoos then you’re choosing to consent to the judgment; you just have to be confident and strong.”

Come time for the job search, Corrado will voluntarily conceal her ink, but will maintain the hope that, at some point, her workplace will welcome her art.

Unfortunately, Lingerfelt says, probably weekly he has clients talking about missed job opportunities because of tattoos. The flip side of that coin is that employers may be the ones missing out on very talented and articulate potential assets.

Cpt. Greg Dobbins of the Floyd County Police Department oversees a work environment where not only are visible tattoos unacceptable, but leniency is also not an option. Officers with visible tattoos on the arms must wear a long-sleeve uniform year round; any other level of visibility (ears, neck, hands etc.) is prohibited. Potential officers must reveal in their applications any and all visible tattoos with an explanation of each, thus beginning the process of acceptance or dismissal.

“I’ve never really been involved in the final decision making,” Dobbins says. ”I’ve been on hiring panels before where we ask questions, but usually by that time they’ve already been weeded out as far as if they have [visible] tattoos.”

Dobbins agrees that the decision of dismissal on the grounds of inked art would be a difficult one to make, but he attests that the County sticks to the policy.

“The perception behind [tattoos] still hasn’t caught up to where we are today,” says Lingerfelt’s wife, Janielle. “People have preconceived notions of what a person with a tattoo is like.”

Twenty hours and one dissertation short of a Ph.D., Janielle is a school psychologist by trade, and is currently contracted by two private psychology practices. With prominent portrait tattoos on the tops of each foot, she proudly pays tribute to her first two Boxer dogs, her “babies.”

Having experience in both public and private work settings has exposed Janielle to contrasting standpoints. “It seems that in a private setting you encounter less difficulty, less stigma, compared to the public school system,” she says.

For Leanna Stinson, a masseuse and manager at Ciao Bella on Second Avenue, private businesses are the way to go, as she says she never encounters any issues with her visible tattoos. With art on each of her inner arms, she says her clientele – the more affluent type – accept her tattoos as part of her personality and trade. But Stinson, who notes that she takes pride in her personal appearance, makes a valid point regarding others’ views on those with visible tats.

“It’s how you portray yourself,” Stinson says. “If you have a tattoo but you’re dressed nicely, people are going to respond to you differently. You can look professional with tattoos, or you can look skeezy.”

Rachel Tanner solidified her professionalism to her clients before revealing her sleeve of colorful sugary treats, a commemoration to her late father who favored sweet flavors. When she first started bartending at La Scala Mediterranean Bistro on Broad Street, she had to wear a cardigan until 10 p.m. for the sake of staving off negative public opinion. But in this small town restaurant and bar scene, Tanner and her customers got to know one another. Over time, she inched her cardigan sleeves up further and further, only to find that her customers treated her the same and only made positive mention of her tattoos.

“I think that was my transition in La Scala,” she smiles. “… gaining respect from the customers first, letting them get to know me, and then showing them my tattoos.”

Tanner knows that the transition was so smooth because not only had she gained trust and respect before revealing her tats, but also because she had presented herself in a confident, respectful manner. “I like that I can show them now,” she says. “It’s literally a commitment and I worked hard to get them.”

Could we possibly be moving toward an era where ink is as acceptable on your surgeon as it is your stylist? For Bradford, the jury is still out on that one.

“It’s hard to say,” she muses. “Bias or acceptance of art on someone who is a scientist versus someone who’s in a more creative field – I’m not sure how to assess that. Maybe in a few years that may change.”

But not a mile away from the sterile walls of Floyd Medical Center, Nicholson, in an equally clinical environment with a more jagged edge, sees society a bit differently.

“The world is slowly coming around to realize that there are tattooed people in it and that they’re not all thugs,” he says. “It used to be sailors and bikers and criminals. We’re not all criminals. Now it’s more like, ‘Why don’t you have a tattoo?’”

Corrado, on the other hand, says while those with ink hear more positives about their tattoos than negatives, they can still discern harsh glares toward their art. “I agree with the idea that tattoos are becoming more accepted,” she said, “but I also think that there are a lot of things that go unsaid.”

For hundreds of thousands of years, tattoos have dotted and decorated the skin as permanent embellishments for the sake of therapy, protection, adornment, commemoration, and symbols of love and belief. And while these purposes reflect positive intentions, the general consensus conveys that, depending on the environment, tattoos remain taboo.

Whether it be McMorrow’s ode to the swirled strokes of a masterful work of art, Tanner’s collaged sweet-tooth family tribute, or Corrado’s whimsical, seafaring leg sleeve, these fine-lined colorful banners will have to stay hidden … for now. VVV

For a consultation at Eternal Expressions call 706-232-8999 or visit the gallery online at www.eternaltattoos.net