The tiny black dial, ‘tick, tick, tick,’ and wait for the soft, blue glow. When the consumer calls, natural gas delivers; not at all unlike the commercialized quick snap of the fingers, emitting the immediate energy that heats your home, cooks your food and powers your vehicle. The consumer, however, may not always be aware of the supply or space from which their resources are recovered. Deriving its form deep below the earth’s surface, natural gas is an energy efficient fossil fuel, spawned as layers upon layers of decomposing plant and animal material are exposed to intense heat and high pressure over time.

The capture, production, and consumption of natural gas is far from a new concept; for more than 150 years, this resource has been retrieved from its earthly depths by manner of well digging and drilling. However, the idea that it could be captured and produced via northwest Georgia soil is an approach untraveled, until now.

In case you didn’t know, we’re standing on it right now. Under our shoes, beneath our side- walks, below our roads, yards and waterways, lies more than 500 million years of geological history. Reaching from lower Alabama up through Northwest Georgia and into the southern tip of Tennessee stretches a Cambrian Age, sedimentary formation known as the Conasauga Shale. What does that mean? For petroleum geologists like Jerry Spalvieri, it means opportunity.

Buckeye Exploration, Spalvieri’s Oklahoma-based oil and gas exploration and production company, is introducing itself, one by one, to Floyd County residents via proposal letters for land lease. Buckeye is on the market for mineral rights in the Rome area in efforts to explore and test for oil and natural gas – resources that have yet to be produced in this state.

As north Georgians are faced with the possibility of the very land on which they stand being the pierced portal through which this resource flows, education and awareness will become much more significant than ever before.

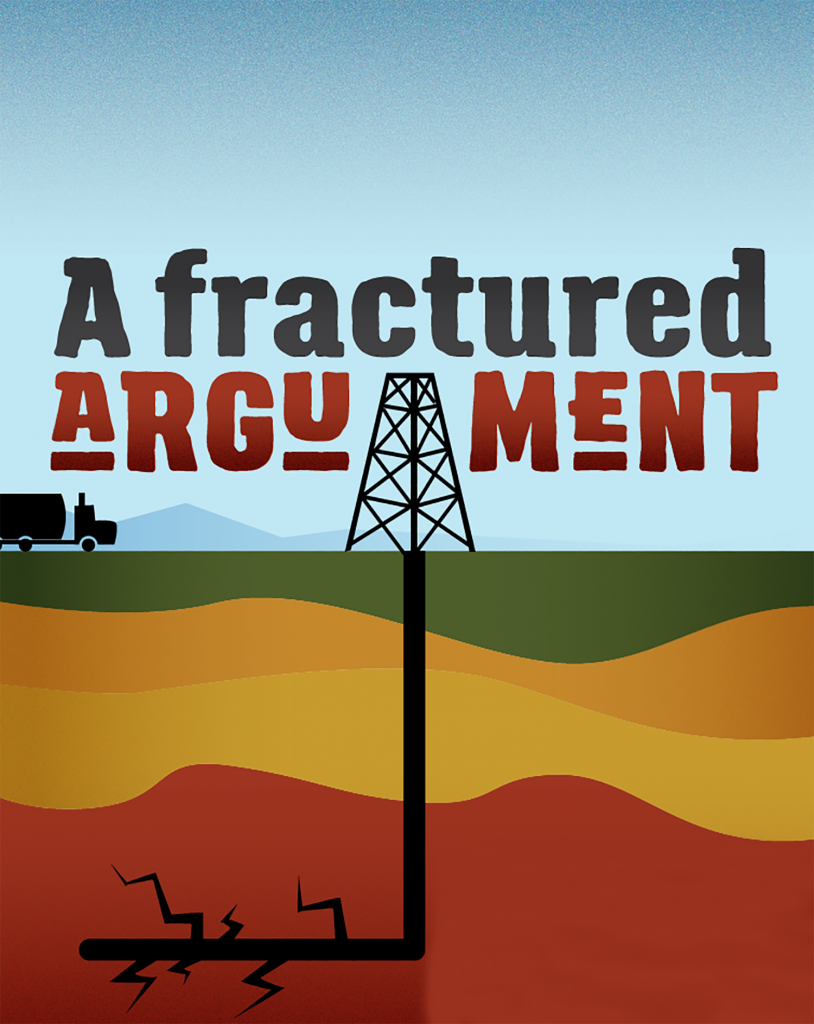

In an ever-evolving world where the unconventional plays a pivotal role in advancement and innovation, the acquisition of natural gas is no different. As knowledge and technology fuel progression, more efficient methods of exploration and seizure arise – like the highly controversial method of capture, called hydraulic fracturing (or fracking).

During the fracking process, it’s known that millions of gallons (per well) of highly pressurized water, sand and unspecified chemical agents are forcefully injected into a wellbore, creating cracks in the thick rock formations through which the gas can then, more freely, flow. To increase the efficiency of the process, the chemical composition of the fracking fluid serves to extend fractures, add lubrication and carry proppant (sand grain) into the cracked rock formations in order to maintain the fissures. Fracking is most often times coupled with horizontal well drilling, where the path of the vertical well changes direction – covering, as they say, a larger perpendicular “pay zone.”

While some may argue that natural gas production via horizontal drilling and fracking has or will reenergize economies, providing an easier, cheaper way to recover a natural resource, the controversy comes in the form of pleas – pleas for the consideration of human health and environmental safety. Horror stories come in clusters, from contaminated drinking water in southwestern Pennsylvania, to seismic activity (earthquakes) in Oklahoma, to toxic fracking fluid spills in Texas. Pennsylvanians in towns like Dimock have said they can trace rashes, dizziness, and headaches, among other ailments, to the toxins that have found their way into their residential wells.

Dr. Brian Campbell, associate professor of anthropology and director of the environmental studies program at Berry College, says one of his biggest concerns with the fracking process is the vast usage of water and the disposal of fluids once they’ve been injected into the well and resurfaced. “When that water comes out, it has got mercury and lead and volatile organic compounds in it that it has interacted with in the ground,” he explains. “Then, they have to dispose of all that as toxic waste. A huge expense on that industry is how they dispose of that water.”

One method of disposal is deep well injection, which is exactly what it sounds like.

“That was the thing that really triggered my irritation and my nightmare experience with hydraulic fracturing,” Campbell recalls. “We lived right by an injection well. When I say right by it, I mean several miles, and we started having earthquakes.”

At the time, Campbell, his wife and his two young children lived in the Fayetteville Shale area of Arkansas, where he previously taught at the University of Central Arkansas.

“Where we lived, they didn’t even have the foresight to do any research on whether or not there had been earthquakes, and there was a swarm of earthquakes in the 1980s in the exact location where they put injection wells,” he says. “So, that’s why we had such large earthquakes, because it was an existing fault line. So, they were just injecting all this lubricant and creating more movement.”

Campbell says the seismicity was constant; category twos and threes were occurring daily.

Although Floyd County residents have not gotten an exact answer on where Buckeye intends to lay the groundwork for drilling, a supposed “target” area is off of Highway 140 around Gaines Loop and Erwin Coker roads, between Woodward Creek and the Oostanaula River. Riverfront residents Kikki Tucker and her husband, Craig, have received one of Buckeye’s oil and gas leases, and Kikki stands firm in the fact that her concerns far outweigh any positives to come from drilling in this area.

“Though Buckeye tried to sell the potential for a positive economic impact, they spoke mostly of bringing in their friends and their crews from other states, so I don’t expect that local employment would be impacted significantly,” she says. “Furthermore, they are only offering $5 per acre for the lease plus a negligible percentage for any oil or gas extracted. Even for the participating landowners, I believe that most of the financial gains will go to individuals and companies that aren’t even from Georgia.”

Nostalgia, livelihood and legacy rest on the soils of this southern land; to some, it means everything. It isn’t difficult to find a voice in our community that raises its tone against the method of hydraulic fracturing; educational gatherings on this controversial process have been hosted by Rome’s own Coosa River Basin Initiative, and the community has established a “Don’t Frack NWGA” Facebook page. The looming question– the elephant that has long since left the corner and is now traipsing through the living room – is “will fracking take place here?”

John Absalon, retired geoscientist and part- time educator at Tellus Science Museum, says that hydraulic fracturing is actually not necessary.

“We find that in the Marcellus Shale [up north], most of the natural gas there is what we call adsorbed; there’s a lot of organic carbon in the unit, and that grabs the natural gas and holds the gas,” he explains. “So, not only does the formation have to be cracked in order to reach the gas, but chemicals need to be added in order to promote the release of the gas; none of that is necessary here. Eighty-four percent of the gas in the Conasauga group is what we call free gas. Only 16 percent is adsorbed, and the unit is naturally fractured.

“In fact, in many areas of the Conasauga, if someone tried to hydrofracture, they’d fail be-cause their fracturing agent would be lost into the natural fractures,” he adds. “They couldn’t pressurize a borehole in order to fracture the rock because all the pressure would be lost into the natural fractures. I don’t know any driller who likes to just throw money on the ground; if they don’t have to do it, they’re not going to do it.”

While the intrinsic fear of hydraulic fracturing runs through the mind fields of our rural residents, Spalvieri says that Buckeye’s plans for the obtained leases here in northwest Georgia are far from fracking. “People are hearing the word fracking and they don’t know it or understand it,” he says. “In this case, we have no intentions of doing any fracking, so they’re afraid of something that’s not going to occur.”

He explains that Buckeye’s intentions are merely exploratory – involving a conventional method of vertically drilled test wells. “I’ve been on this quest to do a conventional prospect in the southern Appalachians to find and discover oil and gas somewhere where it’s never been found before, basically doing it like they did 100 years ago – using basic geological principles, studying the rocks, studying the structure, and understanding the tectonics of the region,” Spalvieri explains.

He adds that his company is too small an entity to ever take on a project that involves fracking and horizontal drilling; a wildcatter at heart, he says that he’s in it for the sake of discovery.

For his conventional wells, Spalvieri uses an air rig that, he says, is bigger than a water well rig, but similar, and that the entire project would use the space of about half an acre. An example of Buckeye’s work can be found just around the corner, so to speak, in Dalton, Ga. Nicknamed the Daphne-Mayfield, the vertical well in Whit-field Co. was drilled 5,000 feet deep in 2010 and, apparently, has found gas and oil without any grizzly headlines of which to speak.

If, in fact, Buckeye does not plan to practice hydraulic fracturing, but the question concerning Rome residents is “will anyone else?”

“The leases that give Buckeye the right to drill allow for Buckeye to assign the leases to third parties,” Kikki says. “The leases also extend indefinitely if Buckeye or their assignees find oil or natural gas. What is implicit here is that, if Buckeye finds oil or natural gas, they will assign the leases to larger companies who will have the right to set up more invasive drilling operations (including fracking) and will also allow for the installation of additional infrastructure to capture, store, and transport the oil and/or gas.”

Kikki’s concerns span water safety, effects on property values and threats to Rome’s tight sense of community; for the most part, her neighbors echo her cautious sentiment. “Some have been

on board with the proposed drilling and have signed mineral leases,” she says. “However, I think the majority of riverfront property owners fall somewhere on the continuum between hesitant and wholeheartedly opposed to drilling.”

With 35 years in the oil and gas industry, the voiced concerns of citizens are nothing new to Spalvieri. “Not everybody is against drilling,” he asserts. “It’s kind of a 50/50 deal.”

Whether 50/50 is a reality or not, it is evident that there is much to learn on the topic of drilling for oil and gas, and there is no shortage of opinion. Documentaries reign as sources of insight; however, unbiased they are usually not. One film of journalistic intent may show a family in Pennsylvania with illnesses and discolored, possibly contaminated, water that at the strike of a match will catch on fire as it streams from the faucet (although it has been found that methane in water wells is an age-old issue, unrelated to drilling or fracking), while another will show a farmer working their land with a sticker that says “Gas saved our A$$” on the back of a mud-clad tractor.

These are the items through which members of a community must sort – gaining a personal, logical working knowledge of what energy means to them and what obstacles seem reasonably worth the reward. Renewable versus nonrenewable energy sources, environmental effects, personal well-being and the future of alternative resources in America should all weigh in on that working knowledge.

It is important to note that there are 67,000 acres of mineral rights just within Floyd and Chattooga counties that are owned by a real estate and natural resource company out of Austin, Texas, called Forestar. While they didn’t respond to V3 for comment, Absalon has interviewed them on their intentions, in the past.

“They’re kind of sitting on the issue right now,” he explains, “because natural gas is less than $2 per unit, and in order to develop new wells, the pipelines to tie the wells together, compressor stations, treatment plants, storage facilities … all the infrastructure, gas would have to be up around $7 per unit (a unit is 1,000 cubic feet or 1 million BTU).”

For decades, natural gas has proven to be a clean, efficient biogenic resource (producing half as much carbon dioxide per unit of energy in comparison to coal); however, it is still a nonrenewable fossil fuel. It has been estimated by the U.S. Energy Information Administration that as of Jan. 1, 2013, there were about 2,276 trillion cubic feet (Tcf) of technically recoverable resources of dry natural gas in the United States.

At the rate of U.S. natural gas consumption in 2013 of about 27 Tcf per year, estimation says that our nation has enough natural gas to last about 84 years. The actual number of years, however, will depend on the amount of natural gas consumption each year, natural gas imports and exports, and additions to natural gas reserves.

At times, natural gas is referred to as a “bridge,” of sorts, to suffice while the U.S. transitions from coal-burning to renewable energy sources like solar power, wind power and/or biodigestion processes.

As a community, the most important thing to be done is to attempt to better understand the science behind these processes and the level of necessity and sustainability present. When that tiny black dial is turned, ‘tick, tick, tick,’ it’s up to us to know where, how and at what cost our resources have been recovered.