Photos by Cameron Flaisch

The cool cascade of a Sunday afternoon rain falls across our shoulders and into our glasses; black coffee and sweet Grand Marnier. A tiny blue notebook collects droplets on the patio table; the ink-scrawled questions inside have been abandoned. This is no longer an interview. It is the purest of exchanges; a sharing of life experiences and raw human emotion, accompanied by a weighted realization that the plan in that blue notebook was entirely naive.

Two thousand words will not do this justice. In fact, there are absolutely no words that could effectively convey the monolithic magnitude of this story. It is one of incomprehensible trauma, formidable loss, overwhelming affliction, and astounding resiliency. It could be your story, but here on these pages, it belongs to Shammah Autry.

A sliver of sun cuts across the glass table in Shammah’s backyard as she and Clint Dillard, her boyfriend of five years, sip the warmth of their coffee. Shammah laughs as she offers up the comedic disclaimer that she is not wearing a bra. Still smiling, she adds that she’d given herself that “gift” even before all of this; and by “all of this” she means her visit to Emory University Hospital in October of last year for a double mastectomy. In July 2017, Shammah was diagnosed with triple-negative breast cancer, and since then, her life’s path has taken many unforeseen turns. This aggressive disease, however, is not her first experience with traumatic, life-changing events or diagnoses; it’s just the most recent.

Sitting beneath the soft rain, fear holds the request for detailed accounts at bay; the last active intention is to retraumatize. But it seems as though that’s not even an option. The time to give voice to these experiences has arrived. Do they define her or speak for her? She will tell you, openly and honestly, that it is not about definition.

“I think, convert to water,” Shammah says. “I think experiences definitely have to change you but they don’t have to stop you. They just change your path a little bit.”

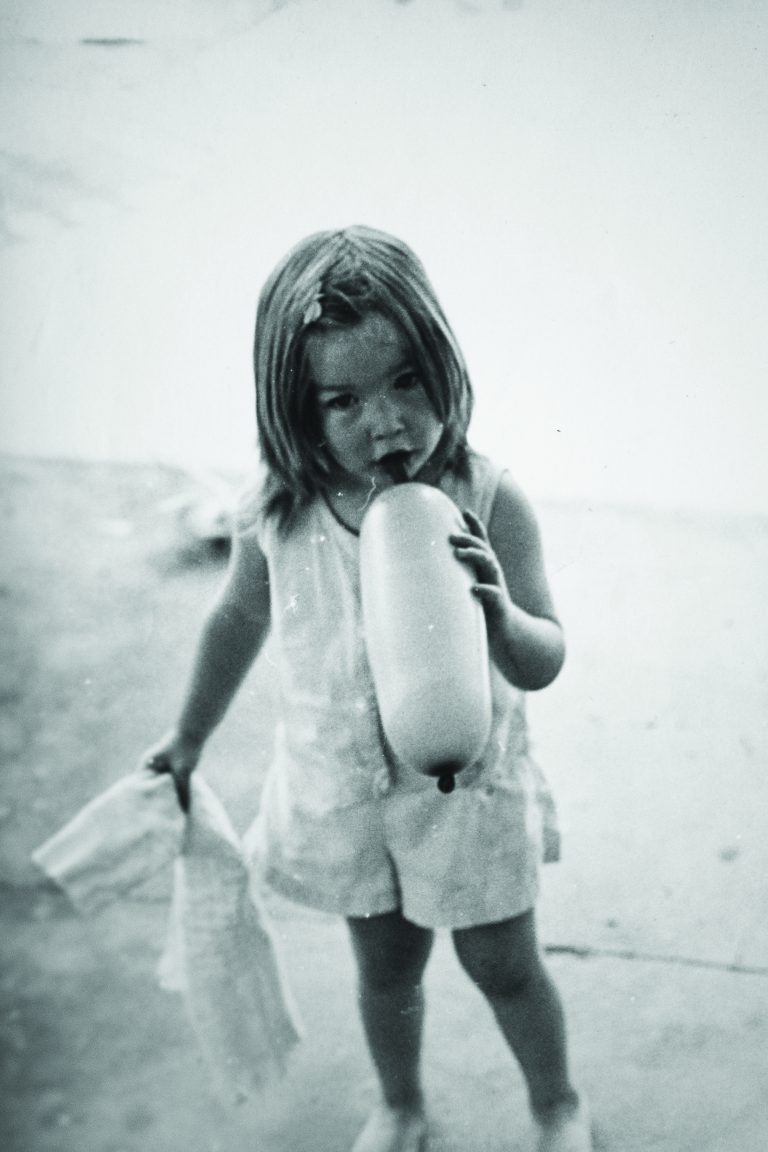

The shapeless yield of flowing water is all too familiar for her. An eight year-old Shammah had to convert the day she said goodbye to her mother…on the kitchen floor of their home, where Jayne Townes Autry had been murdered by the blade of an intruder. White nightgown turned red from her own wounds, Shammah left her mother to seek help. Witnesses that day attested to a calm, collected child who did the only thing she could do at the time, tell the first person she saw. Dillard takes Shammah’s hands into his as he recalls the first time he noticed her scars. He gently runs his fingertips over the remnant of one of the eight stab wounds Shammah endured on that night in 1981.

The scars that travel up the right side of her body are just the visible ramifications of her sustained injury; the internal toll was yet to be revealed.

“Onset from the trauma, my body went into shock because it was protecting itself. I had a lot of stab wounds,” Shammah affirms. “I was in shock and I think it just shut my body down. Within about a year, I was diagnosed with [Type One] diabetes.” Trauma-induced diabetes (especially Type One) is a theory with countless experiences to support it, and it’s one that Shammah fully believes in. This diagnosis has had many years to run its destructive course; beta cells in her pancreas destroyed one-by-one, straining her kidneys to filter harder and harder. Diabetic complications led Shammah in and out of the hospital and, over time, the functionality of these organs continued to weaken.

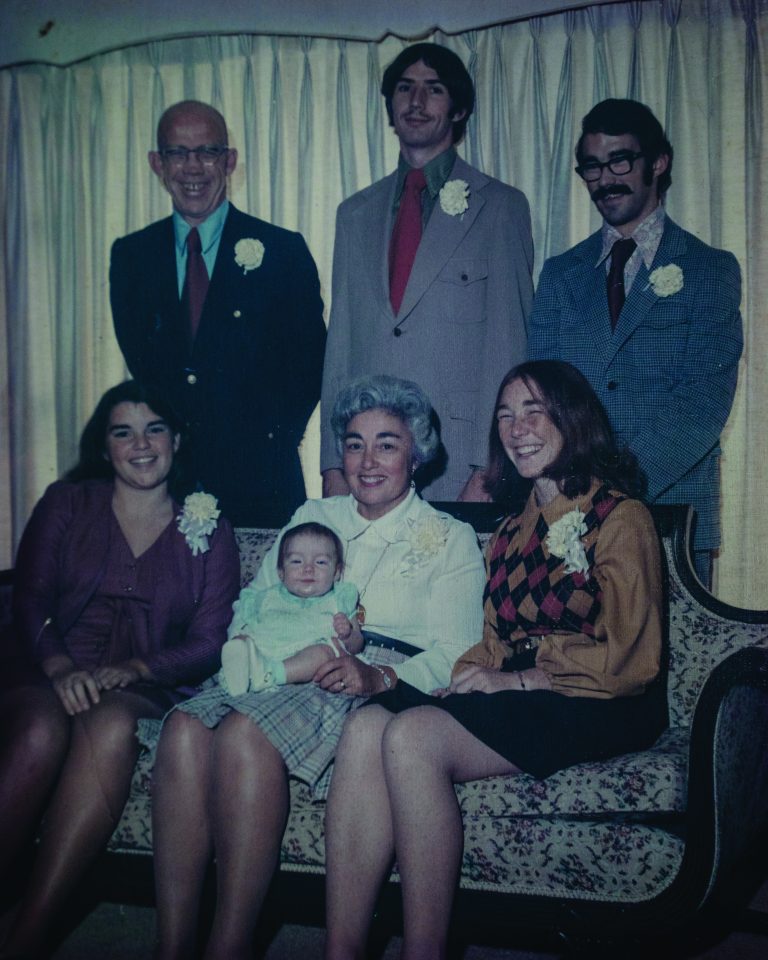

In the spaces between, more life was happening, and nothing stopped Shammah from grabbing it by the proverbial balls. She grins and says that she left Rome, at age 18, in search of “adventure and underlying love” after graduating from Darlington School in 1990. That was the point at which her cousin (and a strong piece of her support system) Jessie Reed, remembers her young adoration for her cool older cousin, whom she looked up to; a free spirit like her mother, according to family members.

“She was a rock star in my head,” Reed smiles, “…just this amazing person who would give me music for Christmas and teach me art. She would sit and draw with me on family vacations. Shammah and I have always been close; we’re more like sisters. She’s 11 years older than me, and she was like my hero as a kid. I just thought she was the coolest thing ever. I mean, I still do.”

Shammah didn’t return to Rome until her late-twenties, when she was able to, both, offer and receive support from her grandparents who had raised her. After the birth of her son, Sam, Shammah finished what she had attempted to start at age 24, she went to school to become a massage therapist. For 12 years, she has been a healer in the Rome community, far beyond the bounds of her schooling.

“There’s the physical work that she does with massage therapy, which is incredible, but then there’s the conversation that she has and the comfort that she would offer,” Reed explains. “Anybody who would see her would feel instantly close to her and connected to her, and accepted. She helps you see your own inner beauty, because she sees it.”

“Knowledge is power, for anything, but your spirit can be used for good,” Shammah says, “…all you have to do is give your energy, intention and direction and it will take. Your intention is a lot more powerful when it’s pure.”

Dillard can also attest to Shammah’s healing power; it’s one of the reasons he fell in love with her. “I’ve seen people come out of massages with her, and they look like they’re high,” he smiles. “They’re hungry, their hair is messed up, they’re flush. She’s amazing. And that’s part of her own healing too. If something was wrong with her, before all of this, she would give a massage and be fine. The energy going back and forth just seems to work it out.”

He looks at Shammah and adds, “The knowledge is technique, and everything else is being honest from the inside.”

In all she does, Shammah maintains a strong love for touch, connection and communication and she believes that what she is going through will only make her a more empathetic therapist.

Given the physical exertion that Shammah puts into each massage, however, she has not been able to work in several months. Sitting up straight in her patio chair, she rubs her slender legs with the heels of her hands, as if charging her muscles; there is much more to tell, here.

The diabetes wasn’t done with its debilitating damage. It was roughly a year into Shammah and Dillard’s relationship that her kidneys finally failed. In March 2014, she began the grueling treatment of dialysis. Shammah’s name remained on a transplant waiting list for both a kidney and a pancreas for several years…until finally, a call.

“This past Memorial Day, it’s 1:00 in the morning,” Shammah recalls the moment. “Clint and I are sitting around playing guitars, singing, hanging out, and the phone rings and they say, ‘Come get some organs!’”

She remembers tears of both happiness and disbelief as they awaited the moment when she would be diabetes free for the first time since she was 10-years-old. But Shammah did not receive those life-changing organs that day. Four hours into their waiting, she and Dillard received another call…the call that told them the organs didn’t make it through procurement and were no longer viable. However, that moment of crushing disappointment and confusion turned into a surreal silver lining just days later, when Shammah received her cancer diagnosis.

“If you get your transplant and something happens and your organs fail,” Shammah explains, “you have to go back to the bottom of the transplant list. Cancer probably would have caused it to fail…and the anti-rejection meds they would have had me on to accept the organ, would have allowed the cancer to just eat me alive.” She pauses, shrugs her shoulders and smiles, “Things happen. And they happen like they’re supposed to, even when it seems like it’s all just sucking.”

Although she does have to be five years cancer free to receive a transplant, she will not have to begin again at the bottom of the waiting list.

After the cancer diagnosis, Dillard says everything went so fast; “freight train after freight train.” The chemotherapy began in September, the double mastectomy in October, peritoneal dialysis all the while, which led to peritonitis (an infection in the inner wall of the abdomen) and set back weeks worth of chemo treatment. Shammah’s hopes of holistic treatment were dismissed, “I looked up so many things.” She holds up her index finger and thumb, “I came this close to buying a ticket to Tijuana.” She recalls being on the website to confirm phone numbers and addresses, and then read the contraindications at the bottom of the page…listed are transplant patients and diabetics. She is currently going through her last several rounds of radiation.

The exhaustion from chemo, the torn tissue around her hip joints from dialysis medication, the atrophy, the terrifying falls, the time spent in a wheelchair, the month spent in agony from a pinched nerve, “Even through that,” Dillard says, “there wasn’t a day that went by that she didn’t smile at some point. Even if she slept most of the day, then woke up in pain, at some point you could make her smile.” Laughter is definitely an important element in the Shammah/Dillard household.

Dillard says that people often tell him that he takes really good care of Shammah. He smiles as he says, “You wouldn’t say that if she were a car,” they both laugh as he continues,” She wouldn’t crank, and the lights aren’t on and the tires are gone!”

“Yeah, you’re taking really crappy care of me, man,” Shammah returns, “You need to park my ass in the garage!”

“Never a dull moment,” Dillard shakes his head. Shammah is out of the wheelchair now and using a walker. A visit to their home may mean that you catch a glimpse of her revving up her engine, walker in hand, and vrooming across the floor!

Shammah does admit that she’s feeling fragile these days; the feeling of invincibility she once had has changed a bit. “I can’t even wrap my head around what she’s had to go through,” Reed says,” but she doesn’t take it personally. She just accepts that that’s what has happened. It’s hard to feel sorry for yourself when you’re around Shammah, which we all have a tendency to do. It’s fairly natural and she doesn’t do that, so being around her makes you feel stronger.”

Shammah says she has always found strength in simple things, like social interaction, driving with no direction, sunshine, and ocean water. One thing she greatly misses is dancing. It seems that no matter who you speak with, this community has one common word that they use to describe Shammah…light.

“I think people see that light,” Shammah affirms, “but I think it’s a reflection of themselves, because people drop their walls when they’re around me. And honestly, what we put up to cover our true selves is, typically, way more ugly than what’s under it. Even if it’s scarred or blemished, that doesn’t make it ugly, it just makes it real.”

“Shammah’s very blunt, open and honest, and I think that’s what a lot of people like about her,” Reed adds. “The first time they meet her they feel like they’ve known her forever.

“She is herself, and she’s not apologetic about it. She’s loving and kind and it gives people around her permission to be themselves….that’s what authenticity does.”

There are days when tensions are high and pain is excruciating; days where those who love Shammah have moments of disheartened spirits and utter disbelief as she faces yet another heinous obstacle in her life path. But there is nothing in Shammah’s voice or vibration that yields to self-sympathy. Pity is unwanted, prayers (no matter the type) are welcome, and hugs are always ideal. “I am a positive, silver lining gal,” Shammah says, matter of factly, “and my life’s just been full of them.” She smiles wide and says, “In the words of the Grateful Dead, ‘Once in a while you get shown the light in the strangest of places, if you look at it right.”

If you would like to give some love and some much needed help to Shammah and her family during this trying time, leave her a positive message or a donation @gofundme.com/ukfave6.