Photos Cameron Flaisch

Despite the rich Native American history that Northwest Georgia has, there are very few remnants of the nations that lived here before us. But somehow, in the middle of busy Cartersville, Georgia, there sits a historic site called the Etowah Indian Mounds. This area is well-known to the locals, and many residents have visited the landmark through school field trips and weekend explorations. We visited the site and spoke with curator and Interpretive Ranger Keith Bailey about the history of the site.

Bailey has been working at the historic site since 2010. He began as an intern and has been the interpretive ranger since 2013. He says the best part of his job is “trying to educate the kids about the society that was here before them.” During the school tours, they focus on three main areas: a tools and weapons program, a tour of the mounds and a film. “If it’s a cold rainy day and they don’t want to do [the mounds], we take them through the museum,” Bailey says. “The site film we’ve actually added online. But there’s other activities that we can do. It’s just a matter of trying to cover all of the curriculum for the grades.” School groups come in numbers of about 75 kids per group, and Bailey says that school groups are huge contributors to their yearly numbers.

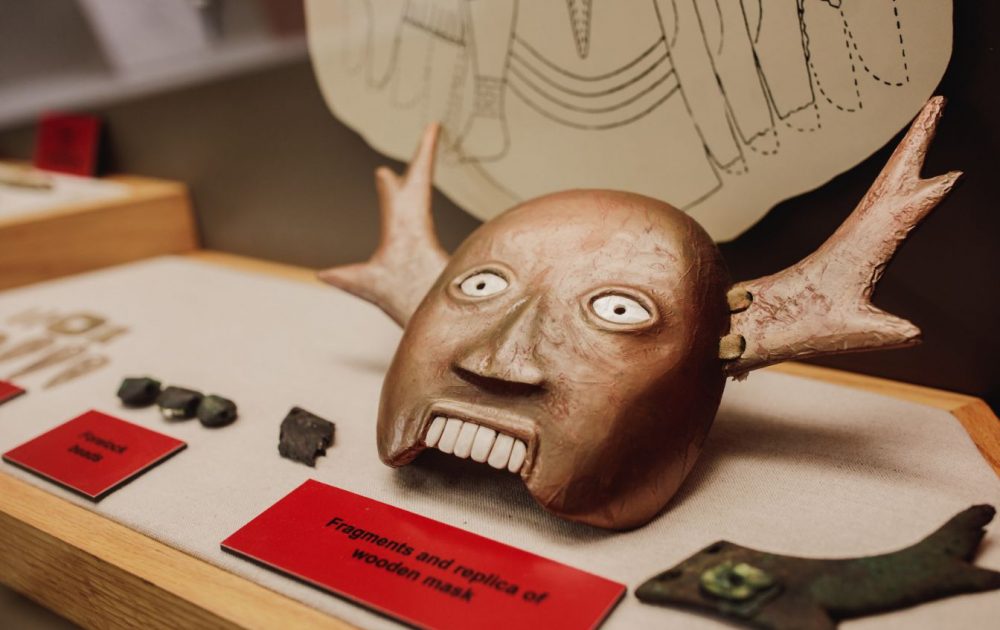

In 2018, they had 11,518 visitors, and they had a goal of 15,000 for 2019. These numbers include school groups, of course, but also local visitors, people from out of state and a good many Native American visitors. The site hosts many events throughout the year as well. There are several Etowah Heritage Days where patrons can learn about how the Native American culture still impacts our area today, as well as the Celebrate Archaeology & Artifact Identification Day on May 2, when people can bring in artifacts for authentication and identification. These events are led by local scholars and historians that can give insight to the history of the culture that was lost.

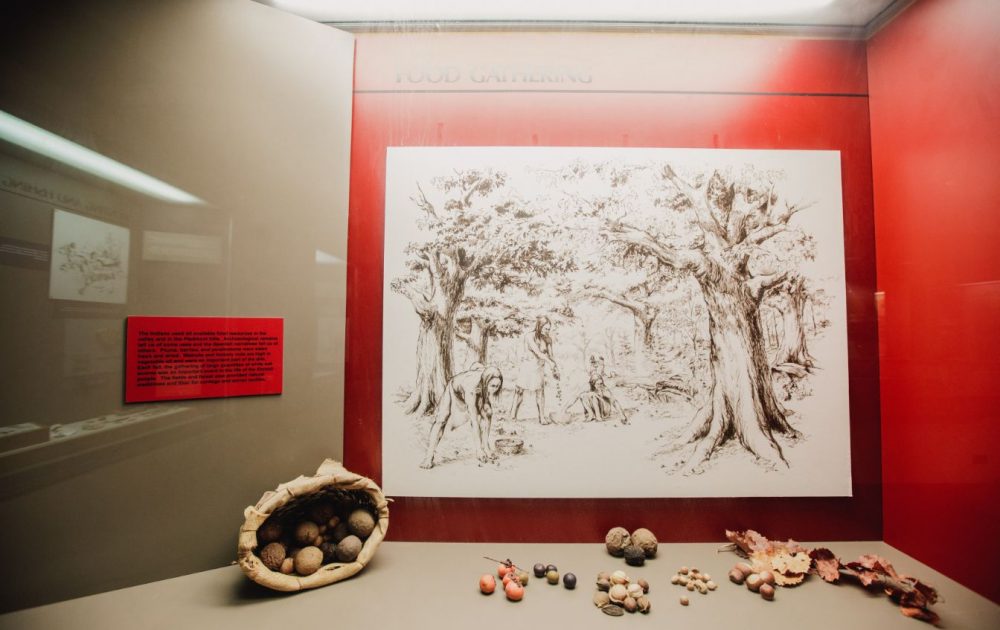

When you see the mounds, they are very impressive and a little confusing. You begin to question why they exist and why they were built. Bailey gives a glimpse at the history of the Native Americans that lived in Northwest Georgia and how the mounds came to be. He begins after the Ice Age: “the Etowah Valley – running through Floyd, Bartow and Cherokee County – are three of the counties in North Georgia that actually have evidence of people being here hunting megafauna such as mastodons,” he says. A mastodon skeleton on display at the Tellus Science Museum in Cartersville was found at Ladd’s Mountain, according to Bailey. “My understanding was that Native Americans utilized the cave that used to be in Ladd’s Mountain, and there used to be a small Woodland Period Mound that was the Shaw Mound. So, we know that people were here in this area hunting mastodons, peccaries and other animals that don’t exist here anymore,” Bailey says. Evidence that such animals once lived in the area has been found in other caves in the area.

A site near Ladd’s Mountain called the leak site is evidence of settlements along the rivers that would have been major cities, according to Bailey.

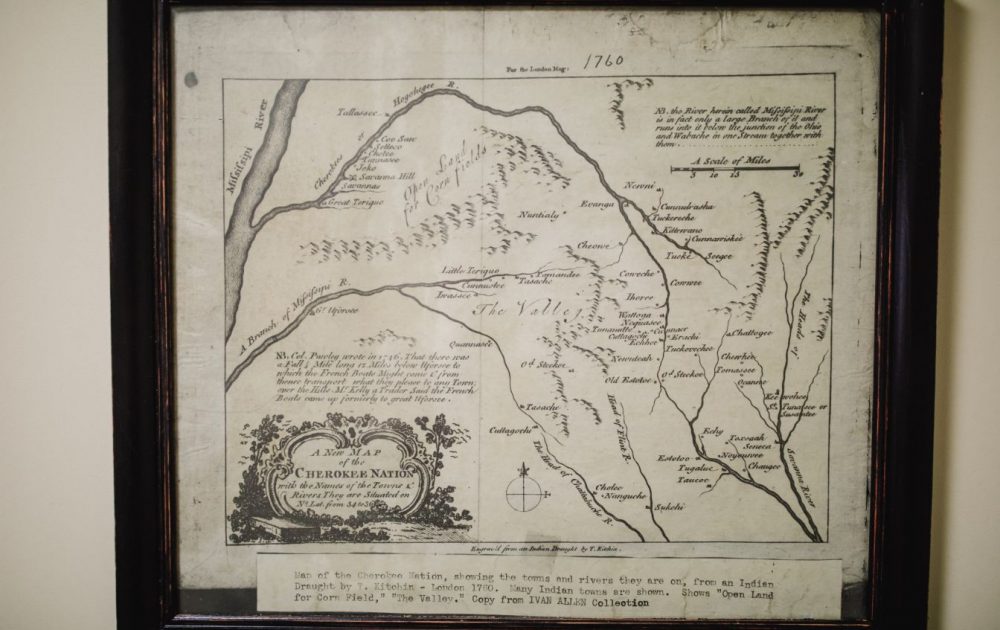

“It dates from about 300 B.C. to about 680 A.D.,” Bailey says. “People would have been using that as a major city in this area and then something happened and they abandoned it… around 800 A.D. we see that there were people living in our area here, and around 1000 A.D. they made this their capital town and they started to build the mounds here.”

Bailey says that the site along the Etowah River was likely a Native American religious and political capital from about 1000 A.D. to the late 1300s or early 1400s. A fire, whether an act of war or intentionally set when the village was abandoned, seems to have destroyed the town at the end of this period, leaving it uninhabited for a while.

“But by the time you see Hernando DeSoto come through the area in 1540, this seems to be a secondary village that’s been re-inhabited by some people and the main town for this chiefdom,” Bailey says.

It’s difficult to comprehend the extent of the society that resided in this area before our modern society, but the Native Americans are a very spiritual and intentional people who worship the earth that provides for them. It makes sense that the Mounds were built with that in mind.

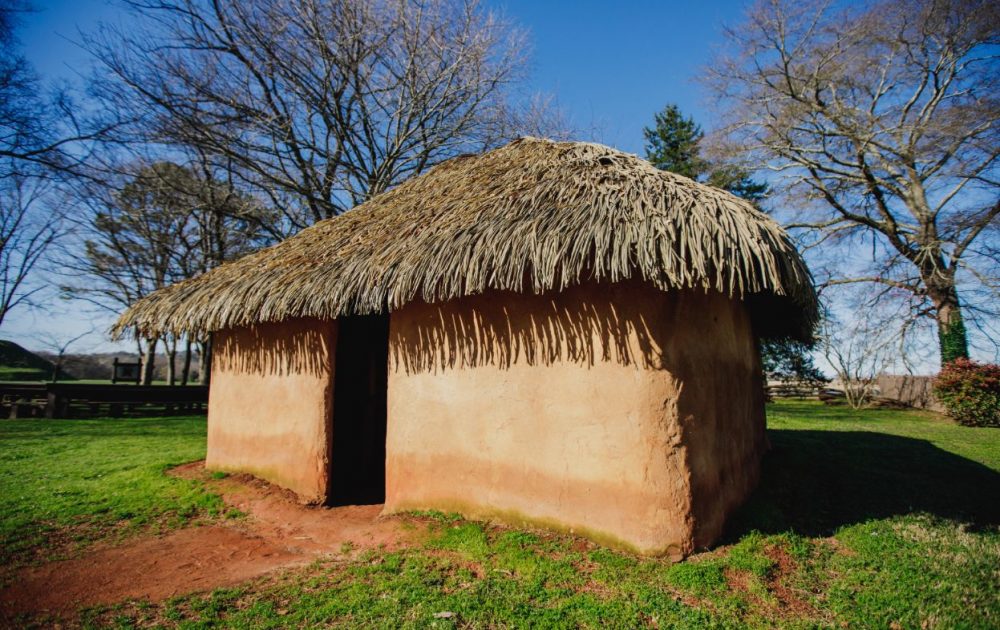

Bailey explains of the mounds that the Native Americans learned that fish could be used as fertilizer. “They built fish traps to collect fish, and then burning produces really high-quality almost like modern fertilizing practices,” Bailey says. “So, they would dig a ditch around where they want their big village and they would use that dirt to build mounds for their Chiefs to live on and their priest to have temples on; basically your political buildings like council houses.” The idea was two-fold: to elevate these important figures out of the flood plain, but also to increase the status of the person living on the mound.

“It seems, in their religion, that they believe that the sun in the sky was their ancestor,” Bailey says. “It was a way of venerating their ancestor and the chief who was a descendent of that person.”

The mounds have been studied over the years. In the 1800s, a flood in the area damaged one of the mounds and unearthed a few bodies. That’s when Bailey says that the Smithsonian Institute stepped in and started collecting artifacts and doing their own research. After a while, they stopped digging and then something changed. Bailey explains that “King Tut was discovered over in Egypt and they started digging in the mounds again because they resembled the pyramids with a flat top. People thought maybe the ancient Egyptians or somebody else had been here.” While this was happening, the stock market crashed and that put an end to this exploration for a while. Later, Mr. Henry Tumlin, the owner of the property, decided to sell it to the state.

“He sold the majority of what is now the park and a few years later he donated another 10-plus acre, and now we have what you see today,” Bailey says. Bailey and his team now take care of the mounds and work hard to preserve what’s left.

You can visit the mounds for a more extensive history and see firsthand what was left behind for us to learn from. The historic site is open Tuesday through Sunday from 9-5. For more information about the park and events, please visit their website gastateparks.org/EtowahIndianMounds