Photos Andy Calvert

According to a U.S. Department of Justice report on state prisoner recidivism, 45% of prisoners released are re-arrested within a year, within nine years 83% recidivated.

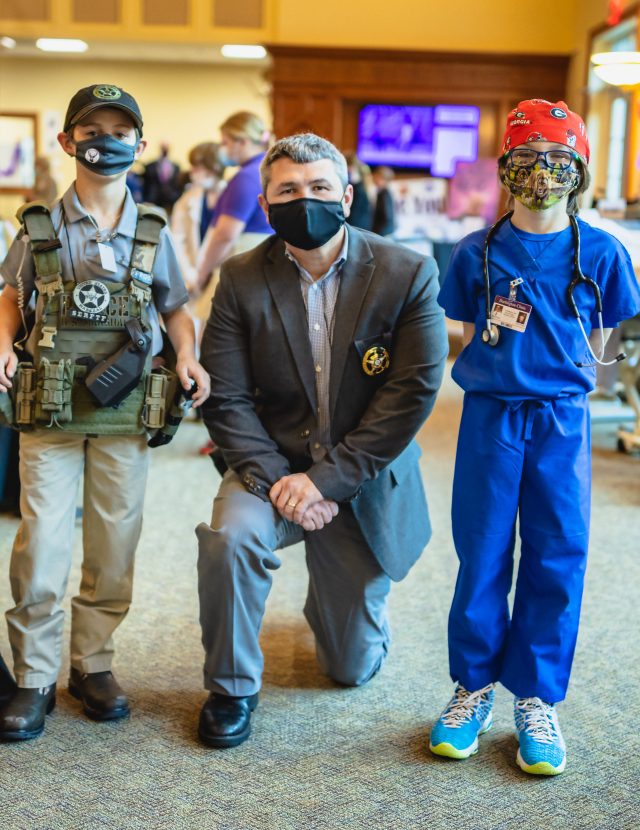

January 1, 2021, Dave Roberson hit the ground running as the Sheriff of Floyd County. His plans to lower recidivism, a discharged offender’s relapse into criminal behavior, rates at the Rome Floyd County Jail are gaining traction and speed with a rally of supporters and activists in tow. Not hesitating to address the complicated issue of mental illness in the jail system head on, Roberson sought the expertise of National Alliance Mental Illness (NAMI) to inform new programs at the Floyd County Jail.

For Roberson, law enforcement has been a way of life since he was a boy growing up in rural Polk County. His father, the late Lonzo Roberson, joined the Rome Police Department shortly after returning from deployment in Vietnam, and proudly served Rome/Floyd county for forty years. “He would bring my brother and I to the office, where we were exposed to a lot of the leaders in the department like former Chiefs, Hubert Smith, Joe Cleveland, Elaine Snow, and Denise Downer-McKinney.

I saw leadership at its best, firsthand. We got to hang out with them in the office, and then later at the ballfield when they played their league softball games. I saw how law enforcement shaped my father and supported our family. After I graduated school, I thought this life was for me as well,” recalls the sheriff. Twenty-six years into his career as a deputy with the Sheriff’s office, Roberson proudly honors his Vietnamese American Heritage as the first person of color elected to hold the office of Sheriff. that made the largest impact.

“I am the kind of leader who leads by example. I am reserved, calm, and steadfast. I will never ask anyone to do anything I myself am not willing to do; I work for the people. The people I work with, I serve them, not the other way around. Most importantly, I make sure that I am always approachable,” says Roberson.

Approachable indeed, it seems he is everywhere these days, local school functions, church food drives, community meetings, and non-profit/ advocacy Zoom calls. One could say he has his ear to the ground and finger on the pulse of Rome/Floyd county. A quiet man himself, it’s clear to see his eyes are sharp and ever watchful over the community he loves so dearly.

“Now more than ever, community engagement is everything. Law enforcement and public safety has to be involved in community events and programs, otherwise you wouldn’t know the needs and you would just get lost in it all,” says Roberson. He stays involved whenever opportunities are offered to hear public opinions and recognize the issues that have public traction. “A primary issue I see that our community faces relates to mental health,” states Roberson.

The goliath issues of mental illness awareness, limited resources, and lack of funding for community programs plagues not only our community but our country at large. These issues impact individuals, families, and prove devastating on the jail system, which ineffectually becomes housing for many who need treatment and services, not sentencing.

Bonnie Moore, Program Coordinator with the Rome chapter of National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) paints a bleak picture wrought with pitfalls, saying, “Many people with a mental health issue don’t know they have it. Highland Rivers CSB is the only provider in Floyd county to provide care for mental health, developmental disabilities, and addictive disorders for those without insurance. Many people are not educated about mental illness, and family members give up on them. The system lets them down. This can often lead to homelessness, and criminal behavior.”

The new medical and psychiatric facilities built by 2013 and 2017 SPLOST funds have allotted the Sheriff’s Office with the capability of more appropriately serving its numerous inmates who cope with mental illness. In conjunction with this effort, Sheriff Roberson has worked alongside Moore for over twenty years. Most recently they joined forces in providing Crisis Intervention Training (CIT) hosted by the Floyd County Police Department.

This training detailed and presented methods for field officers from numerous agencies to quickly identify a mental health crisis, introduce helpful interview strategies that allow for de-escalation and avoiding rushed procedures. Sheriff Roberson is utilizing the expertise of NAMI to integrate education programs for the jail staff and field deputies in an Introduction to Behavioral Health and Addictive Disorders course.

NAMI is planning to facilitate peer-to-peer support groups for inmates with mental illness to help individuals identify their illness, available services, and possible treatments; directed by peers who cope with illness and have also been incarcerated. “It is important for people to see others who have shared similar challenges such as mental illness and incarceration now lead functional pro-social lives. They see that their success is possible,” explains Moore.

Floyd County has made an effort to tackle mental health in its adoption of the Stepping Up Initiative in 2018. This is a national initiative to reduce the number of people with mental illness in jails. “Stepping up involved city and county commissioners, other community stakeholders, law enforcement, courts, and judges to look for ways of diverting individuals away from immediate booking, like a diversion center.

The county government is very pro-finding solutions for diversion, besides jail. You are going to have individuals that commit crimes against property, crimes against another person, serious crimes where they will have to come to jail. However, there are some issues that can and should be handled another way, for instance we should not have somebody come to jail for hollering on a street corner, we need to look for other avenues to tackle that,” explains Roberson.

In his first order of business upon his election, Sheriff Roberson established the groundbreaking program F.R.E.E.D. (Floyd Re-Entry Education and Discharge), and named Jenn Cronan Offender Services Unit Manager. The program’s mission is to increase public safety and reduce recidivism by providing positive opportunities to transition offenders from jail to the community.

Recidivism is a central concern for the criminal justice system as it often implicates the effectiveness of rehabilitation and probation programs as well as the performance of prisons. Research suggests those with mental illness have a 9-15% higher likelihood of recidivating than those without diagnoses.

This is the statistic the Sheriff’s Office hopes to tackle in their F.R.E.E.D. program. However, no data has been collected to measure recidivism in Georgia’s jails, making the Sheriff’s Office’s F.R.E.E.D. program the first of its kind. The program is bold and unique in its application to the jail system where mental illness may have a large role to play in its recidivism numbers.

Although similar programs have been created through the Criminal Justice Reinvestment Act which calls for re-entry programs for prison inmates, the jail system follows a different process. Cronan describes, “For one, in prison, inmates have a timeline. There is a set time frame for their release or probation. Many inmates approach services goal oriented. In jail, there is no date. Most offenders don’t know what the next step is. Pre-conviction, there is no specific timeline for when or if they bond out, get sentenced, or have charges dropped.” This is a huge variable to consider with limited resources.

“Sheriff Roberson’s F.R.E.E.D. program is one of a kind that thinks outside the ‘jail housing mentality’,” says Cronan. By February, Sheriff Roberson and the office rolled out phase one of the F.R.E.E.D. program distributing resource packets to those released from jail. Soon, phase two will be in full swing with targeted services and groups to include cognitive behavioral and restorative justice programming. “The significance of this phase is that we can identify what services are currently available to the offenders to avoid lapse of benefits, and also to identify any needs that have not here-to-for been addressed,” explains Cronan.

“Also, in phase two we begin to engage offenders in cognitive behavior therapy to teach inmates pro-social thinking skills. Linking real world problems with responsible and non-criminal solutions. For example, if someone runs out of money a pro-social approach would be recognizing that it’s time to get a job or apply for a loan, rather than an anti-social solution to steal money or to commit a crime.

Restorative Justice therapy primarily teaches accountability by encouraging offenders to look at crime in another way; acknowledging that criminal behavior affects not just an individual but the entire community. We help them dissect behaviors as choices to engage or disengage from a community. In jail, it’s often one will hear ‘I caught a charge.’ as if this is something that happened to them as opposed to ‘I acquired a charge’,” explains Cronan. By changing the verbiage, the jail staff works to change the way inmates think and feel about their circumstances and the power of their choices.

In the Offender Services Unit’s discharge plan, offenders with substance misuse and abuse issues might be referred to local outreach programs for support. For the many with mental illness, their needs are carefully assessed. Mild mental illness diagnoses that allow for individuals to maintain a job may be referred to the Elevation House, a non-profit charitable organization that aims to end economic and social isolation for adults living with mental illness. More severely affected individuals may require a 30-day case management and a referral to the Highland River Center, mental health clinic in Rome. The Sheriff’s Office has worked hard to foster relationships with organizations and businesses that provide housing and medication services. The jail also provides the necessary picture identification cards to avoid any disruption to services, medications, and support.

“None of this would be possible without the close partnership and affiliation with NAMI,” states Roberson. With support of NAMI, the jail has begun the roll out of phase three, connecting discharged offenders with job opportunities. However, there are specific challenges individuals face when they self-identify with mental illness, “People won’t hire them,” states Moore. “The stress and anxiety that comes with a 40-hour work week simply is not doable for some with mental illness.

We look to connect people with split-shift opportunities; wherein two or three individuals can be trained and alternately fill a full-time job position. This enables people to build self-esteem and self-worth. They can earn money and avoid the pitfall of losing and reapplying for disability or social security benefits. There are many other positive implications to this employment model. Last year the National Institute of Mental Health reported a national $193 billion loss due to mental illness, job losses, retraining expenses, and lost income of their caretakers,” continues Moore. Local efforts take broad strokes against this reality.

What’s next for the F.R.E.E.D. program? The possibilities are endless when considering the needs of those who require rehabilitation and support to transition safely into society. “It’s all about coming together and working together. To know what’s happening, see the needs, and engage the community,” says Roberson. Sheriff Dave Roberson remains committed to building relationships and changing attitudes as he shifts the jail from a place that houses people to a place that frees individuals; embracing the opportunity to alter mindsets that keep communities bound.