In the early decades of the 20th century, two women set out to provide care and protection for the children in their communities. Ethel Harpst and Sarah Murphy each opened homes in Cedartown to care for children orphaned by influenza and other diseases that ravaged the area. Though the two women did not work together in life, their legacies merged in 1984 to create Murphy-Harpst, a non-profit organization dedicated to meeting the needs of abused and neglected children throughout the state of Georgia.

Murphy-Harpst continues the work of Sarah and Ethel, working with the Department of Family and Children’s Services and the Department of Juvenile Justice to identify children and youth who would benefit from their programs. The organization has a residential campus, and it also oversees foster homes and community outreach for at-risk youth in the area.

Finding the Right Fit

“We’re in a state of emergency statewide in terms of child welfare,” Advancement and Stewardship Officer Scott Fuller explains. According to Fuller, there are an estimated 15,000 youth in state custody in Georgia, and Murphy-Harpst gets referrals for 1,500 to 1,700 kids each year. Because of the campus’s limited resources, they can only admit about 150 children per year, with up to 60 kids living on campus at any given time.

With so many children in need and a finite number of beds at the Murphy-Harpst facility, Fuller explains that they must be discerning when determining which kids to take in. The Murphy-Harpst admission process takes into account a child’s background and circumstances and ultimately attempts to decide whether the child would benefit from Murphy-Harpst’s specific program, Fuller says.

“That admission process is important because we’ve got a program working here to heal these kids, so we’re having to be very careful about who we place and the time we place them,” he explains. Associate Director of Marketing and Communications Claire Wood adds, “We are meeting very specific needs for very specific kids, so we want to make sure that we’re giving the right kids the right shot. If a kid gets to us and is willing to work the program, once they’re ready, we find that they can really be successful.” Murphy-Harpst may not be the right fit for some youth for a variety of reasons; in these cases, the team at Murphy-Harpst works with state case workers to find a program that would be more beneficial to the child.

Aside from their residential campus, Murphy-Harpst also places children in foster homes in the community. The organization currently has 50+ children in 25 foster family homes. In placing children in these homes, the organization pays particular attention to keeping siblings together. “We specialize in sibling groups,” Wood explains. “We have one family that recently took in a family of five, from itty bitty baby to age 12 or 13.

We have families that will say ‘We want to keep these kids together,’ and we prioritize that wherever we can.” According to Fuller, the ultimate goal is to transition these at-risk youth from state custody to a family home, whether it is their home of origin, an adoptive home or a foster home. “We are dealing with kids who are in trauma, so we’re trying to keep them from those higher level of care places,” he says. “We’re trying to move kids away from those paths and back down to paths of a family home and successful living. We’re kind of that last stop.”

Individualized Care, Community Atmosphere

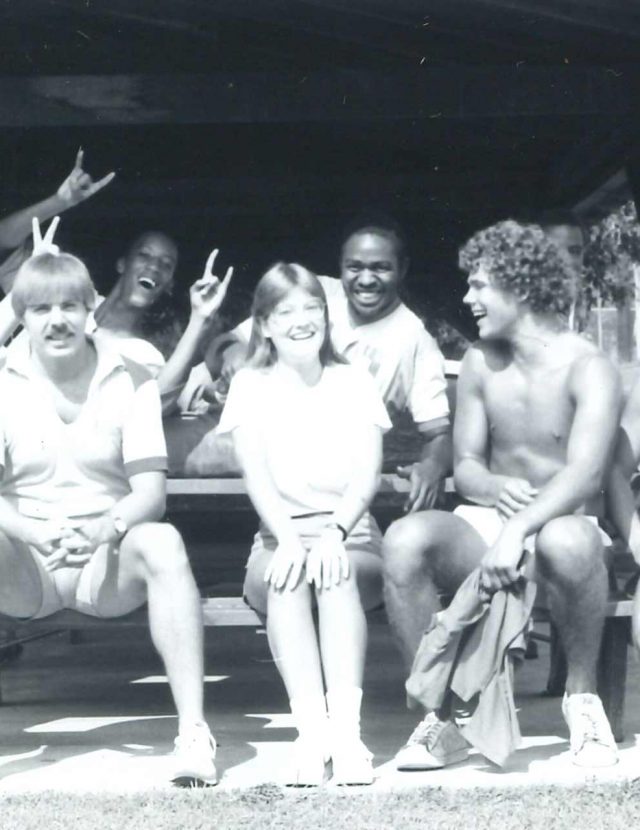

Murphy-Harpst aims to provide its residents with a welcoming environment and a comfortable structure in which to process trauma and move forward. Several cottages serve as homes for the youth on campus. Guided by cottage leaders and assistants, the youth take care of their own rooms, assist with household chores, and participate in recreational activities with housemates. “We’re very deliberate in how we go about that kind of schedule and experience,” Fuller explains.

In a typical day at Murphy-Harpst, the kids help with chores in the morning, attend school for most of the day, and then have recreational activities after school. These activities cater to a variety of interests and also help the residents in achieving their personal goals. “Our recreational program is broken up into different activities that are suited to a child’s interest or the cottage’s interest,” Fuller says. “Some will be at the equine center learning how to take care of a horse, some may be in the gym or on the ball field, some may be having music lessons in the chapel.”

Each resident has individual therapy sessions scheduled throughout the day with one of Murphy-Harpst’s therapists, but they also often participate in group therapy in conjunction with recreational activities. “To make them more able to hear their therapist, to be able to express themselves with a therapist, to talk about those hard places and how to cope with these thoughts or these fears — having those moments with a horse, with that therapist in a recreational environment, enables them to begin to receive the therapy,” Fuller says.

Certain activities like animal assisted therapy lend themselves especially well to these types of therapeutic encounters, according to Fuller. “A dog or an animal is calming,” he says. “It’s your best friend; he’s not going to hurt you, he’s going to help you.” This is especially evident at Murphy-Harpst’s equine center. “Our kids will bond with a horse before they’ll bond with an adult,” Fuller says. “They’ll whisper in the ear of a horse something they’d never tell an adult.”

Making Strides

The unique services available at Murphy-Harpst do wonders for these kids. From small, meaningful steps in therapy to huge leaps into adult life, Fuller and Wood have seen many children make life-changing progress because of Murphy-Harpst.

One child, Joshua*, arrived at Murphy-Harpst at the age of 13. Full of anger and trauma from his past, his struggled to acclimate and was prone to outbursts. His second week, he was working with a group at the equine center, learning to saddle the horses. Joshua grew frustrated, threw his saddle down, and started walking away. Blaze, the horse he was working with, followed him and nudged him. Joshua saw Blaze but continued to walk. After Blaze nudged Joshua again, the equine instructor said, “Blaze wants you to put the saddle on him.

Blaze knows you can do this.” Joshua immediately broke down in tears. “It was a moment for this young man to really settle into our program,” Fuller says of the moment. “For the first time, somebody cared about him; somebody valued him, wanted him, and was pursuing him in a way that nobody ever had before. With a therapist there and in an environment like this, it’s one of those pieces that’s significant, life-changing.”

In 2017, Murphy-Harpst introduced the Transitional Living Program (TLP), yet another resource that allows at-risk youth and young adults to benefit from the organization’s services. Older teens who are on the verge of “aging out” of state care now have the option to stay on Murphy-Harpst’s campus as part of this program.

The TLP allows these young adults to join an educational or a vocational track. They might work toward a GED or a college degree, or they might get a job in the community, all the while learning valuable skills for independent living. Budgeting and bill pay, grocery shopping and meal preparation, job application tips and more are invaluable lessons that these young adults have the opportunity to learn while staying at Murphy-Harpst.

Get Involved

Murphy-Harpst is always open to community support, and there are several ways that you can get involved. Groups often sponsor drives to collect school supplies, recreation equipment, or “build a bedroom” items for a new resident, or they can volunteer to host a birthday party or assist with beautification projects on the campus.

When school is out, Murphy-Harpst welcomes community volunteers who want to assist with recreational activities. “We need the gifts and financial support, but we need the people. We need community on our campus,” Fuller says. “Ultimately, we need more people to be aware of the needs of this population of youth and more communities that are moved to serve them.”