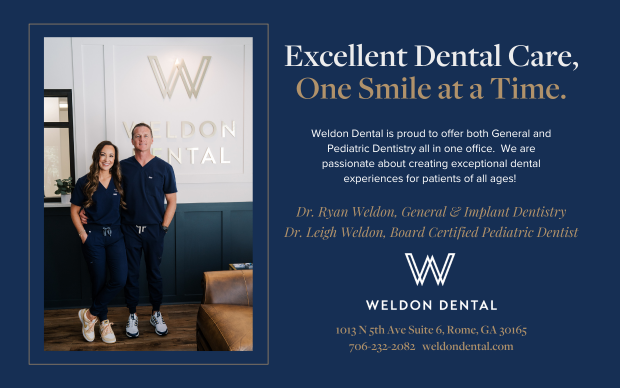

Photos Rob Smith

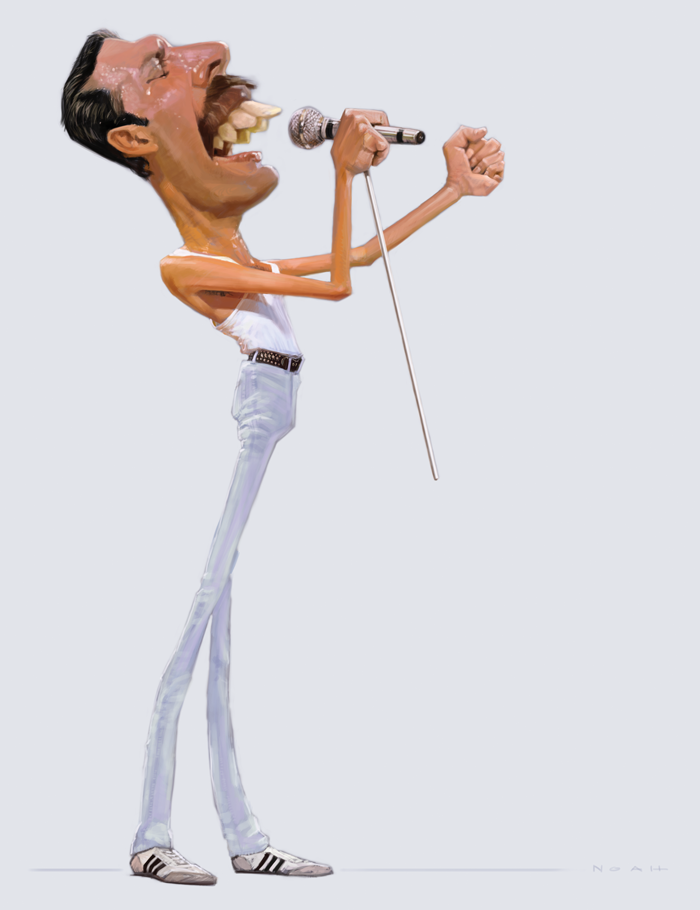

Babe Ruth, Freddie Mercury, Bear Bryant, Clint Eastwood, Michael Jordan, John F. Kennedy, Charlie Daniels, Willie Mays.

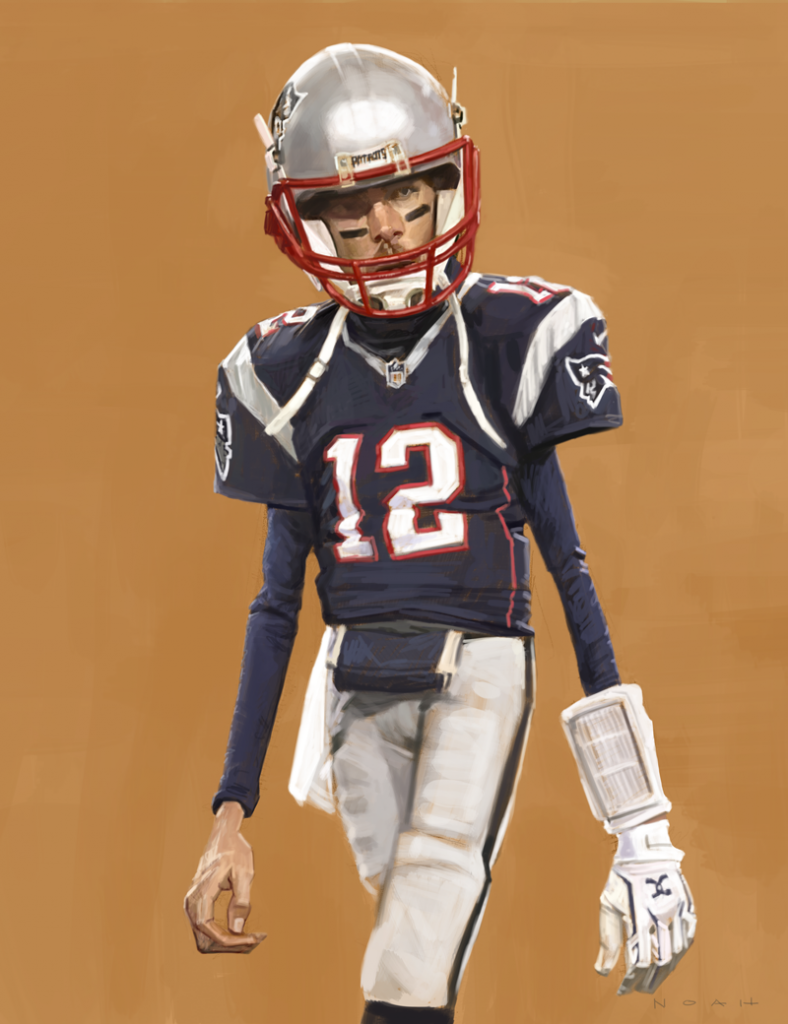

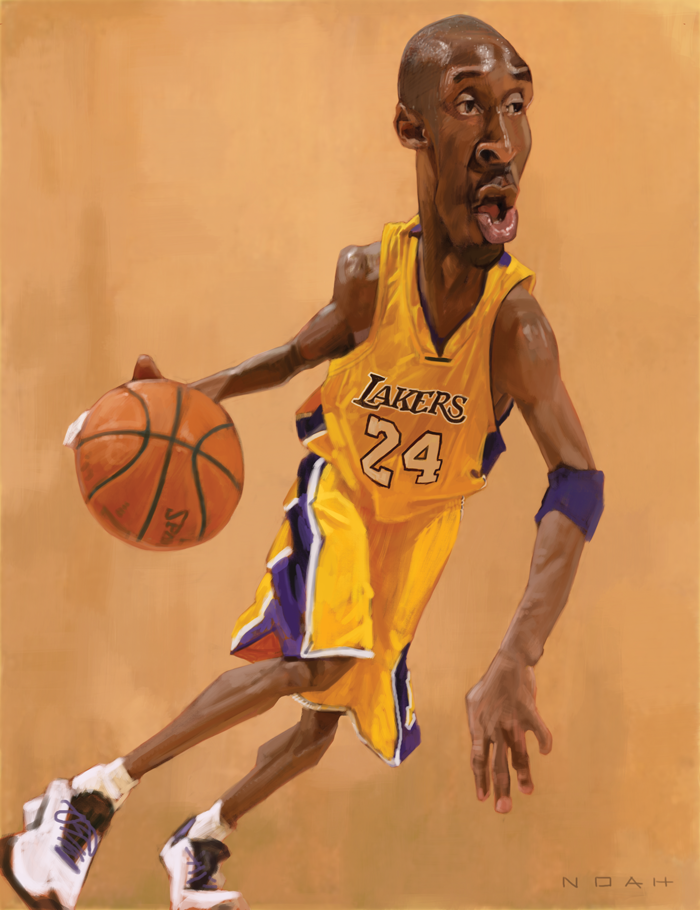

Besides each being a household name and a legend in his own right, what do all these people have in common? They are all subjects of spot-on caricatures by Georgia artist Noah Stokes. These celebrities and many more from the worlds of sports, music, politics, movies, and television are portrayed by Stokes’ signature style that combines whimsy with a healthy dose of respect, even adulation.

His work is a celebration, not only of people’s physical features, but of their fame, talent, ambition, and perseverance. Noah Stokes is a fan of many of the people he draws and paints. That affection, though playful and satirical, comes through in his artwork.

The art of exaggeration

According to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary, a caricature is an “exaggeration by means of often ludicrous distortion of parts or characteristics.” Is that an accurate definition of Noah Stokes’ work? Not exactly. His drawings and paintings carry more nuance than that. This is no amusement park cartoon huckster knocking out quick and easy portraits that capture little more than the obvious. His work is neither flattery nor ridicule. It digs down, looking for something beneath the surface.

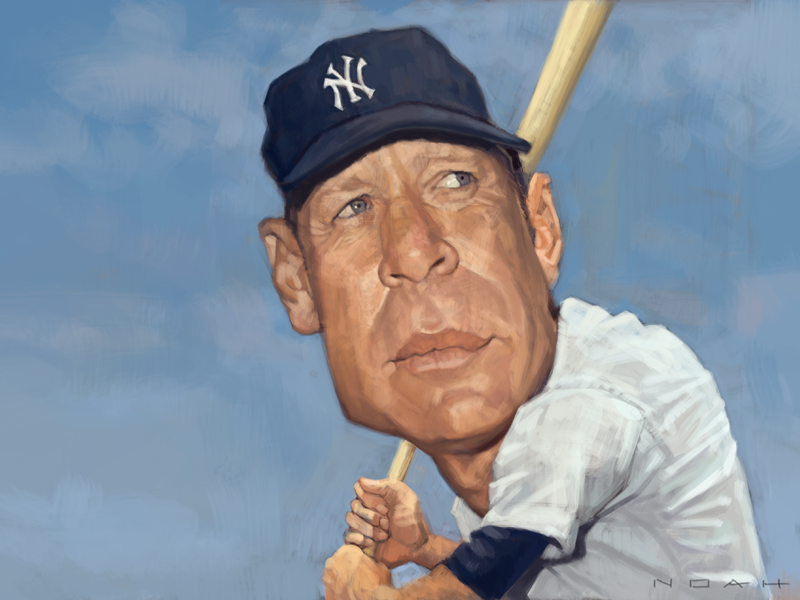

Case in point: Stokes’ painting of Joe Jackson, “Shoeless Joe”, who played baseball in the early 1900s and became both famous and infamous for the Black Sox Scandal (and then was exposed to a wider audience with Ray Liotta’s portrayal of him in the movie Field of Dreams). Stokes’ caricature of Jackson shows more than a mere delineation of his features. True, the picture is, as they say, the spitting image, but it’s more than that, too.

It’s a study in close observation. Stokes has distilled the man’s personality by getting the details right. The clutch of the bat. His deceptively casual stance, like a calm before the storm. The hardness in his face. And that stare—the steely glare that so intimidated the players on the opposing team. It looks like he’s daring the pitcher to throw the ball anywhere but right over the plate. Stokes is not just drawing a baseball player; he’s illustrating an attitude. It’s as much about character as it is caricature.

Stokes explains it this way: “I paint heroes. That’s how I characterize what I do. I use exaggeration to capture those larger-than-life individuals and moments in sports, movies, music. It’s sometimes humorous, but it doesn’t have to be.” For Stokes, he’s not simply satirizing the people he draws and paints. He is portraying their physical characteristics, personalities, and movements as they are—only more so—to tell a story, to explain something to the viewer. “It’s about pushing those things that we all recognize to be true about a face or the way they move that is unique,” says Stokes. “Ultimately, I want to honor those that I paint.”

Finding his way

Though Stokes displayed a natural artistic talent early in life, art was not his first love. “I was not directed to this path in my youth,” Stokes says. “I wanted to be the hero! Sports was my love growing up. School, as it was required, was difficult. It always felt like someone was saying ‘Here is what you are supposed to know, now tell it back to me,’ and I was staring out the window. I could not see the purpose or the benefit of learning things by rote.”

Sports, on the other hand was a way for Stokes to express himself naturally. The rules were clear. The camaraderie was appealing. The expectations were achievable. And best of all, unlike classwork, it was fun. He says, “Sports came much easier; it was an interesting problem worth solving. Somehow, I didn’t realize I could take the same effort, practice habits, and determination and apply them to my studies.”

After high school, Stokes went to college, but he did not immediately pursue the study of art, and his high school disinterest in academics followed him. “I had no business going to college,” he says. “I did everything but go to class. Not proud of that. I felt really lost.” After a couple of false starts, Stokes enrolled at the Art Institute of Atlanta where he earned a degree in visual communication, and that’s where things turned around for him. He says, “It wasn’t until art school that I felt I was on the right path to a career. It was another interesting problem to solve.”

After graduation from art school, Stokes landed a job with a plastics manufacturer, creating package designs, logos, and other visual art projects. He says, “I enjoyed my time as a package designer but always wished I had a more classical training. You say you’re an artist—well, what does that mean? Prove it. You prove it by the work people can see. I was designing cow manure bags and packaging for frozen food—not really something you can hang on your wall as decor.”

Despite the heavily commercial aspect of his day job, Stokes never lost his love for drawing. He knew he was more than a designer; he was an artist, so he mustered his courage and segued into the world of fine art. Combining his love for sports with his drive to draw, he began creating paintings of various sports figures that he knew had a built-in fan base. He launched this new enterprise by producing limited edition prints and selling them through art dealers.

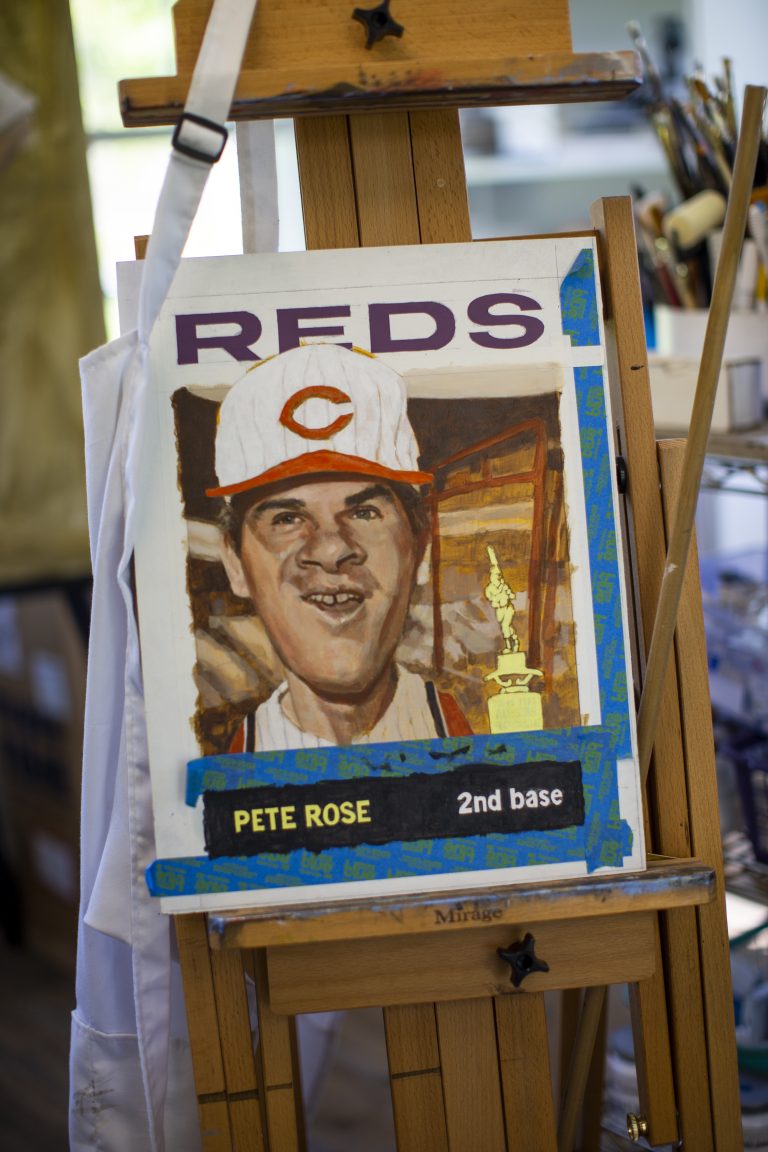

These days, there is no need to doubt Stokes’ artistic chops. Though his style as a caricaturist is well-honed, all his work is not cartoonish in nature; a vein of serious fine art also runs through his portfolio. There is no denying that his work, both fine art and caricature, is now worthy of framing and displaying. Stokes’ website points out that “his work hangs in The National Pastime Museum, The Negro League Baseball Hall of Fame, and the University of Georgia. It is also in the personal collections of UGA and NFL great Herschel Walker, FSU Coach Bobby Bowden, and ‘The Head Ball Coach’ Steve Spurrier.”

In the footsteps of the greats

Stokes’ work pays homage to the greats in the field of illustration, especially to that of Norman Rockwell and Bernie Fuchs. Like Rockwell’s paintings, Stokes’ creations show an interest in human expression (especially in the face), movement, and physical exaggeration—they don’t try to make people look beautiful; they show them as objects of interest worth studying. And like Rockwell’s Saturday Evening Post covers, Stokes’ subject matter has a nostalgic feel to it. In perusing the breadth of Stokes’ work, one is as likely to find persons from some bygone golden era as one of today’s heroes.

Regarding Stokes’ similarity to Fuchs’ work, it is seen in the energetic interpretation of line, shape, and light through loose, expressive brushstrokes. Bernie Fuchs famously admired the French Impressionist Edgar Degas, whose paintings (think of slightly blurred ballerinas) pulsated with a sort of electric energy. Fuchs incorporated that same feel into his work, and Stokes, at least in part, absorbed it into his own creations.

If Rockwell was expression, Fuchs was impression, and Stokes fuses both ideals into his work, making them his own. That’s the way things work in the world of art: one generation influences the next, and inspiration passes down from the old to the young—the process repeats itself throughout history, constantly providing society with new masters.

Room to think

Noah Stokes works from home in a setting that many artists would envy. Though his home is just a short drive from downtown Dalton, Georgia, it feels like it is isolated in the countryside. Part of that impression comes from the surrounding farmland and part of it is from the looming presence of Rocky Face Ridge (also known as Buzzard’s Roost) that blocks out the horizon behind Stokes’ property. The beautiful white wood frame farmhouse where Stokes and his wife, Ruth, raised their three children (Leah, Jake, and Sarah) is, like Stokes’ artwork, a sort of melding together of styles and eras.

The “new” part of the home, the front of the house, was built in 1905. It was an add-on. The original part of the home, which now serves as a sitting room and a kitchen, predates the Civil War. Its origins are mysteriously murky, perhaps Cherokee. The original handmade bricks, which are exposed inside the house, show the scars of the history they’ve lived through and leave questions for the imagination. Stokes’ working studio stands just a few steps from the back door. It is a bright, modest square room, with windows on three sides. All around are drawings and paintings of all sizes: works in acrylic, oil, and pencil.

Putting the work in artwork

One drawing instructor (a cartoonist named Williams) who taught at the Art Institute of Atlanta at the time Stokes attended, used to open his first day of class by writing the word ARTWORK on the chalkboard in large, scrawling letters. He would point at it and say, “See this word? It’s a compound word made up of two words, art and work.” Then he would draw a diagonal slash through the word, bisecting it into two parts. He would say, “Now, if you count the letters in each word, you’ll see it’s more work than it is art.” Williams would go on to explain to his students that it wasn’t art-hobby or art-play or art-inspiration, it was art-work.

Stokes agrees with Williams’ sentiment. He encourages young artists to embrace the work ethic of creating art. For him, it’s not supposed to be easy to learn. It takes training and practice and discipline. “I want people to know that it takes a lot of work,” Stokes says. “It’s like developing any skill; it is developed through repetition. It takes time. There are no shortcuts. I didn’t grab onto everything my dad tried to teach me, but one thing he told me did stick: he always said, ‘You can do anything in this world that you set your mind to.’ When it came to art, I believed him.”

For more information or to purchase original art or prints, go to noahstokesart.com.