Andy Calvert & provided by Dekie Hicks

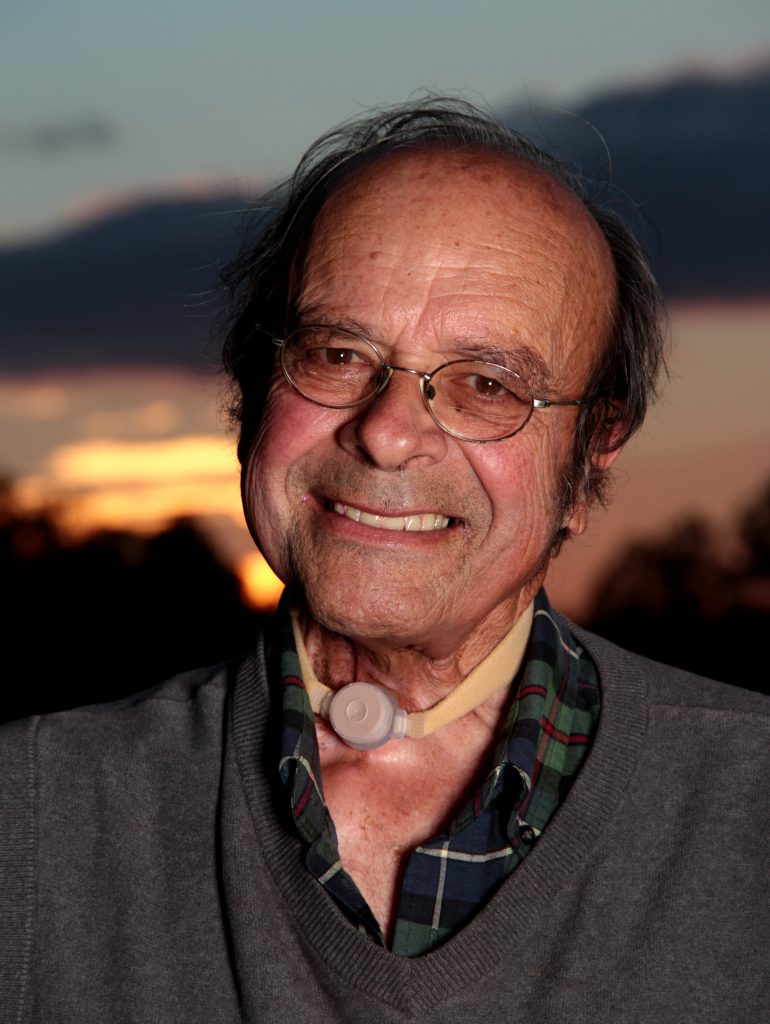

He had a magic touch when it came to living things. John Schulz was perhaps best known in Northwest Georgia as a botanical artist of sorts, that is, a creator of landscapes. But he did not grow up wanting to be a gardener; he came to this field by an unexpected route: photography. In the early 1970s, when he was teaching potential dropouts at Eddy Junior High School in Columbus, Georgia, he took up photography as something to teach his students.

He wound up falling in love with it himself. His pictures caught the attention of a man who hired Schulz to take photos of his wife’s African violets for a book. Though unsure about the project, Schulz went and took the pictures. He was captivated, and from then on, he was hooked on photography. So, his initial interest in gardening was not in planting and designing, but in the beauty of flowers, the aesthetics of plants.

Schulz designed and built a greenhouse at the school where he worked, and it was there he began to teach himself how to grow things. In 1975, with the help and encouragement of some friends, Schulz moved to Rome, Georgia, and opened a greenhouse. Running that business is how he met many of the people around town who became his customers. This began a seat-of-his-pants effort to teach himself how to do beautiful garden design. Through trial and error, he became a master at it.

Over time, Schulz expanded his gardening work to more private homes, public spaces, and even took on corporate accounts (like the area McDonald’s). Eventually, he had a landscaping crew working under him.

Pulling weeds, writing words

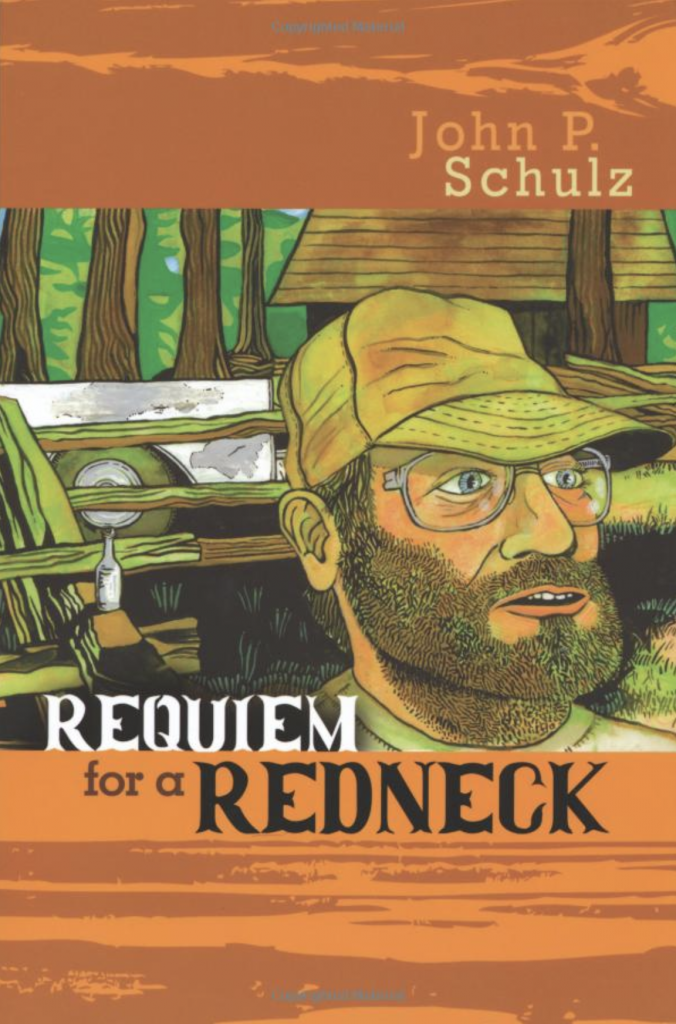

Though widely known as John the Plant Man, Schulz could just as justifiably be called John the Book Man. Dekie Hicks, Schulz’s widow, met him in the spring of 2007. She recalls, “We met at a meeting of RAW [Rome Area Writers]. He was there looking for an editor, and I said I would edit his book for him.” That book turned out to be Schulz’s first novel, Requiem for a Redneck, which was published in 2009.

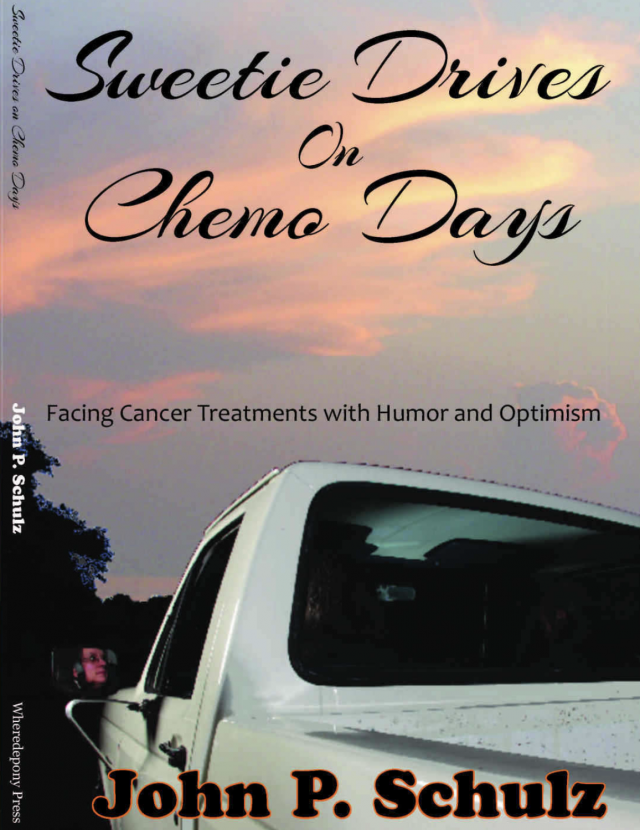

Over the next 10 years, Schulz came out with three other books: the sequel Redemption for a Redneck, an autobiographical work called Sweetie Drives on Chemo Days, and a volume on gardening called The Basics of Pruning. Originally, it was Schulz’s intention to make his Redneck books into a trilogy, but as Hicks puts it, “He couldn’t find the perfect redneck crime. Requiem is a tragicomedy, and Redemption is a love story, and he wanted a mystery, like a crime/caper, but it never worked out.”

Hicks published all of Schulz’s books through her company Wheredepony Press, which provides editing services, book formatting and design, and assistance with dealing with printers for people who want to self-publish. She says, “This business grew out of John’s search to self-publish Requiem. Back then, he was doing a lot of research on self-publishing and came to the conclusion that he wanted to try it. So, when he met me, we decided to try it together. It was sort of a lucky thing.”

Schulz was an active member of the Northwest Georgia writing community, working for years with Rome Area Writers, and participating in local and regional writers’ conferences and workshops. He loved words—the well-turned phrase—and he was a great encouragement and inspiration to many of his fellow authors. Schulz’s personal writing style was both funny and touching, often surprising. It was quiet, unassuming, and unfussy. Like Mark Twain, his stories often ended with a humorous twist the reader did not see coming. Jason Lowrey, former president of RAW, says, “John was the sort of writer and storyteller who made it all seem so easy. He had a great sense of timing and pacing with his writing, because he could keep everyone engaged with a story right up until the final humorous, wry, or poignant moment.”

A writer’s life

Though Schulz was 63 years old when his first novel was published, he had always been involved in the world of the written word. Hicks says, “John has always written little vignettes, told stories, and he loved to read.” She goes on to explain, “Really, it started years ago, when he went off to live with some rednecks after he had some problems. He got divorced and went to live with the rednecks.” Back in the 1970s, Schulz had opened a greenhouse in Coosa and met people who wound up being prototypes for characters in his later novels. “John always had a respect for redneck people,” Hicks says. “He never really made fun of them, and he always differentiated between rednecks and white trash.

To John, rednecks had a bit more pride and savvy in how to keep themselves up, and they didn’t mind working hard. He saw rednecks as people who were unwilling to adjust to the greater society out in the world, with all the weird quirks and rules. John liked that rednecks knew how to do things, fix stuff. They may not be fancy, but they’re self-sufficient, neat and clean. They’re craftsmen who work and pay their bills, but when it comes to stepping up in the world they are perplexed.”

One of the great strengths of Schulz’s fiction was the believability of his characters. A reader familiar with the tri-state region of Georgia, Tennessee, and Alabama would immediately recognize Schulz’s creations as the types of people they saw every day. They had the sound and feel of the rural South. As Lowrey puts it: “What I admired—and envied—most about John’s writing was his ability to capture and depict character through dialog. He had a gift for taking the way someone talked and putting it on the page in a way that made it sound completely authentic. It’s a difficult skill in writing, and John was an expert at it. The way he wrote characters’ voices made them come alive on the page.”

Also, there was an intentional merging of fact and fiction in Schulz’s work. If, for instance, he wrote a supposedly autobiographical piece about an event in his childhood, there was no point in cornering him about the veracity of the tale. To him, that didn’t matter. He was a storyteller, not a historian or a biographer. “John followed the old adage about never letting the truth get in the way of a good story,” Lowrey says, “and I don’t think we’ll ever know how much of his writing was based on fact, how much was fiction, and how the two were blended together. And I don’t mind at all. John used his writing to express himself, find happiness in this world, and give people a good story. How much of it was true, or wasn’t, is irrelevant. But I’ll always remember walking up to him after a Rome Area Writers meeting and asking, “Did that actually happen?” and his only response was a smirk and a shrug. It was a good story, and that’s all that mattered.”

Change and challenge

Schulz was diagnosed with throat cancer in 2010. At that time, he and Dekie Hicks were engaged and planning their wedding. Hicks says, “He did one round of radiation, and then we got married.” After a reprieve, cancer returned in 2012. That was a time of change and challenge for several other reasons as well. Hicks says, “That’s when his son J.R. got married, his brother Billy passed away—of course, his mother had a really hard time with that. Then John wound up having major surgery in September of that year.” Sadly, that medical procedure cost him his vocal cords, and it was five months later before he received a voice prosthesis.

Describing Schulz’s attitude through all of that, Hicks says, “John was a good patient. He didn’t complain. He did whatever he had to do. But he went through a lot. After he got his voice prosthesis, he began major chemo and radiation at the same time.” During this, he drove back and forth to Emory early in the morning for the first radiation treatment of the day. Tuesdays were chemo days, and that’s when Hicks would drive him.

After receiving a five-year all-clear from his doctors, Schulz was diagnosed with prostate cancer in 2018. Hicks says, “That was pretty aggressive, and then it came up in his lungs and in his brain.” Ultimately, Schulz passed away on April 20, 2022, at the age of 76.

One way Schulz dealt with his initial round of treatments was to write the book Sweetie Drives on Chemo Days. Hicks describes this work as “sort of a self-help book. Its subtitle is Facing Cancer Treatments with Humor and Optimism, and it’s a nice explanation of how he dealt with everything. It helps people know what to expect when going through treatment.” She goes on to say, “The book is interspersed with recipes; I did a lot of experimental cooking to feed him. And I wrote the last chapter to help the patients’ caregivers to know what to keep in mind.”

By nature, John Schulz was an ironic humorist, his wit was dry and unexpected. He had an uncanny ability to take awkward, unpleasant circumstances and write about them in a way that made his readers laugh. “I’m convinced the world is a better place because John Schulz was in it,” Jason Lowrey says. “I miss him, his writing, and his sense of humor. If writing is one way to attain some level of secular immortality, John’s achieved it. He deserves it.”

For more information about John Schulz’s literary works go to wheredeponypress.com and johntheplantman.com