Constellations of street signs shift with the passing of time and even smaller scale cities witness the shape-changing evolution of its skyscapes. Whether by aesthetic addition, environmental development or progressive movement, the one constant in every culture is change.

When movements are made of moments and transformation is ever-present, we rely on vibrant memory and preservation of history to show the paths that have been travelled before us. Paths that cut through our current daily view in antiquitous apparition of a past we may not even realize. If you planted your feet on the wintry beige sod at the corner of the current Five Points area in Rome, standing between the newly established Martin Luther King Jr. monument and the Northwest Georgia Minority Business Association sign, would you know on what ground you stand?

Would you be aware that the land beneath your feet, during a Jim Crow South, once served as the hub of African American social and economic livelihood in Rome?

The establishment of the Five Points African American business district was one born of necessity. It is absolutely no secret, and entirely an understatement to say, that the serrated ramifications of segregation forced African Americans to create their own course of action to satisfy even the simplest necessities of everyday life. From the late 1800s and through the tumultuous sixties, Rome’s Historical Five Points area housed a myriad of businesses that saw to the needs and desires of a thriving race, unwelcomed elsewhere.

Chairperson for the African American Historical Society, Rufus Turner, recalls the energy and prosperity of the Five Points from his youth, “Rome was a thriving city for black people back during the time.” Raising his brows and smiling, he says, “Just the number of businesses that were here in Rome, and not only that they were here in Rome, but in the downtown area.”

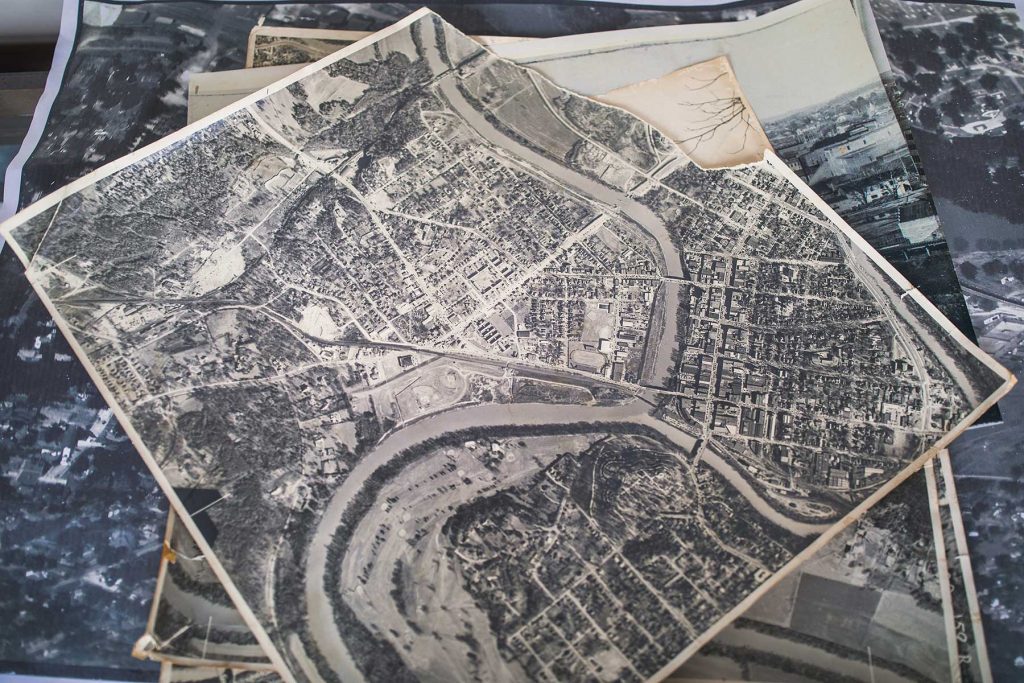

Today, the corner of North Broad St. and MLK Blvd. marks a central spot for the Five Points Turner remembers. Hospitals, churches, restaurants, barber shops, shoe shops, drug stores and even a pool hall scattered across Cothran, East and West Ross, East First, and North Broad; the five streets that converged to form that bustling district of more than 30 different African American owned businesses in its time.

Hubert Holland Jr. recalls the two-story brick corner building with wide glass windows that looked in on the barber shop his father owned, Holland’s Barber Shop. Always full of busy chatter and the sound of scissor snips, Holland says there was never a dull moment in the shop. Politics dominated the talk and there was always a game of checkers or cards to be played.

“I have to say, my father’s barber shop was one of the most modern barber shops they had in Five Points. He had shower facilities for truck drivers passing through Rome; they could stop at my father’s barber shop and take a shower and get a shave, a haircut and a shoe shine,” he remembers. “The most memorable part about the shop,” he adds, “was how he trained other young men to cut hair and be successful. He was all about the education and training…learning a skill.”

Reliving, just for a moment, his days after school at Main High School on East First St., Holland says, “I used to shine shoes in the barber shop for extra money.” He chuckles slightly and adds, “As soon as I made my money, I couldn’t wait to spend it on ice cream cones at the Webb’s Cafe.”

Webb’s Cafe, owned and operated by Gene and Carrie Webb, was a full-service soul food restaurant next door to Holland’s; the cafe was better known as Spider Webb’s (a nickname for Gene). Word has it that the cabbage and cornbread were especially delicious. A tangible souvenir from the era, and a replacement for East First St., is Five Point’s Spider Webb Dr., affectionately renamed in honor of Gene.

The upstairs space in that same corner building, built in 1912 by Dr. Robert N. Brooks, once housed the very first African American hospital in Rome, Brookhaven Hospital. Five Points also saw the era of the Samaritan Hospital as well; how significant an establishment given the fact that African Americans could not be treated in white hospitals.

Bishop Norris Kenney Allen Sr., founder of the Northwest Georgia Minority Business Association, remembers his teenage years in Five Points; getting his hair cut at Holland’s, hanging out at Webb’s Cafe and watching his peers shoot pool at Eli McConnell’s Billiard Room.

Turner says that while each end of town in Rome had a few black businesses, Five Points stood out. He attributes this to the fact that Five Points was a livelier hub with a central location, easily accessible not only by locals but also to travelers passing through.

Turner likens the district to Atlanta’s Auburn Avenue, known as the Sweet Auburn Historic District. Auburn Avenue was a mile and a half stretch of successful African American established commerce and congregation, like Five Points, during a time of restricted laws and vitriolic racism.

“Five Points was a very close-knit community; like a family,” Holland recalls. “There was no animosity, no drama; everybody spoke to everybody and everybody worked as a team.”

A team that local playwright and former Rome City Schools educator, Willie Mae Samuel, says worked to influence the economic wellbeing of Rome and Floyd County as a whole.

“All of the businesses there impacted the economy of Rome because the items purchased from various stores to sell had come out of various wholesale stores locally,” adding that, “Business licenses helped to render funds to the Rome economy. The money turned over in the community several times before leaving.”

The beginning of disbursement for this bustling community began with a plan. Urban Renewal moved through the heart of Five Points with redevelopment intentions for the area that, Samuel says, was a gradual process, beginning in the late sixties and into the mid-seventies.

Allen expresses that the consequences of Urban Renewal on the area meant that many, if not most, of the businesses were not able to regroup or relocate.

While Turner affirms that some of the buildings and houses were in disrepair, the effects of this new city plan were a direct hit to the African American community. “In a way [Urban Renewal] was a good thing, but in a way it was some very important history, as far as the blacks are concerned, that just disappeared as if it never was there.” He adds, “It’s a part of our history that’s just gone.”

“Only one building is left standing,” Allen says, affirming that it is the brick building that once housed Atlanta Life Insurance Company and Lyon’s Drug Store, next to the Masonic building on the cusp of Broad and North Broad…the repurposed brick face of a faded Five Points era.

So many of those who are able to recollect their own personal moments amongst the bustle and business of the Five Points black business district devote their time, effort and memory to preserve its history in some form or fashion.

For Allen, establishing the Northwest Georgia Minority Business Association was a direct result of the disbursement of areas like Five Points throughout Northwest Georgia. From Cartersville to Chattanooga, Allen says the association works to support minority businesses in general, offering resources and education to ensure success as well as providing youth scholarships.

Inspired by the words of a history teacher at Main High School and by a time of resilience and thriving in a place that tells “the history of us,” Turner works diligently on his future book, “African American Footprints,” complete with profiles from The Rome Enterprise newspaper, which was Northwest Georgia’s only weekly African American newspaper and was housed in Five Points as well. Turner, who has struggled with his vision, is now back at his writing desk and hopes to have his book published in the near future.

Collectively, Turner has been gathering information for his book for decades. “I want to try to follow through with the purpose of the Historical Society,” he explains, “making people more aware of African American contribution, especially in Rome.”

Make yourself aware. Allow yourself the privilege to absorb history like that of Five Points and those with whom its memory remains. Read “The Rivers Meet” by Morrell Johnson Darko, grab a copy of “Excuse Me: Extraordinary Journey of my Life” by Norris Allen Sr., keep an eye out for Turner’s book and catch one of Samuel’s plays. As the days of February are fleeting, use your moments to offer reverence, extend respect and engage in commemoration for a history that changed your culture, your circumstances and your skyscapes.